Researchers from China, Canada, and the University of Bristol have discovered a dinosaur tail complete with its feathers trapped in a piece of amber.The finding reported today in Current Biology helps to fill in details of the dinosaurs’ feather structure and evolution, which can’t be surmised from fossil evidence.

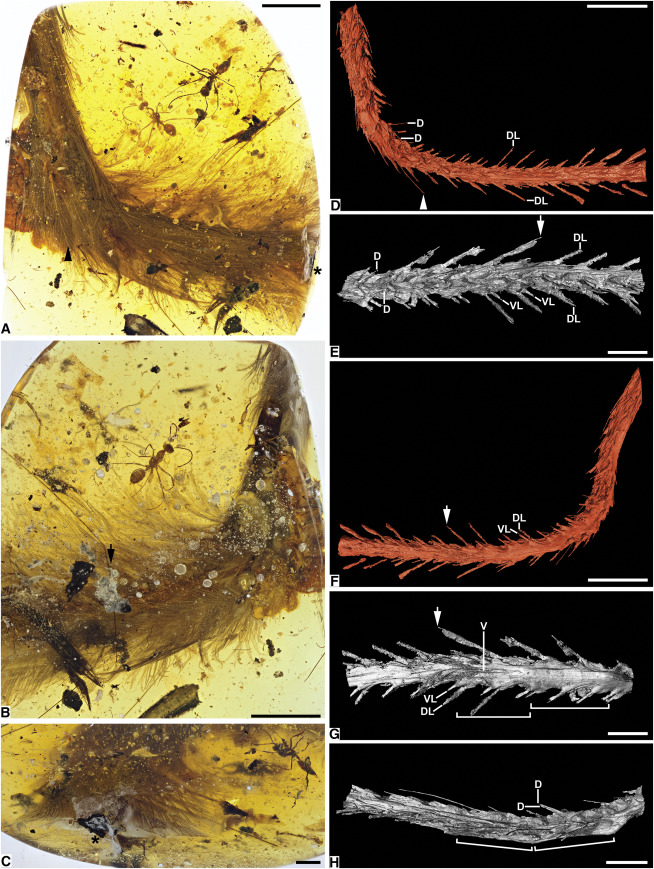

Photomicrographs and SR X-Ray μCT Reconstructions of DIP-V-15103

(A) Dorsolateral overview.

(B) Ventrolateral overview with decay products (bubbles in foreground, staining to lower right).

(C) Caudal exposure of tail showing darker dorsal plumage (top), milky amber, and exposed carbon film around vertebrae (center).

(D–H) Reconstructions focusing on dorsolateral, detailed dorsal, ventrolateral, detailed ventral, and detailed lateral aspects of tail, respectively.

Arrowheads in (A) and (D) mark rachis of feather featured in Figure 4A. Asterisks in (A) and (C) indicate carbonized film (soft tissue) exposure. Arrows in (B) and (E)–(G) indicate shared landmark, plus bubbles exaggerating rachis dimensions; brackets in (G) and (H) delineate two vertebrae with clear transverse expansion and curvature of tail at articulation. Abbreviations for feather rachises: d, dorsal; dl, dorsalmost lateral; vl, ventralmost lateral; v, ventral. Scale bars, 5 mm in (A), (B), (D), and (F) and 2 mm in (C), (E), (G), and (H). See also Figure S2.

While the feathers aren’t the first to be found in amber, earlier specimens have been difficult to definitively link to their source animal, the researchers say.WFS News:Ryan McKellar, from the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Canada, said: “The new material preserves a tail consisting of eight vertebrae from a juvenile; these are surrounded by feathers that are preserved in 3D and with microscopic detail.

“We can be sure of the source because the vertebrae are not fused into a rod or pygostyle as in modern birds and their closest relatives. Instead, the tail is long and flexible, with keels of feathers running down each side. In other words, the feathers definitely are those of a dinosaur not a prehistoric bird.”

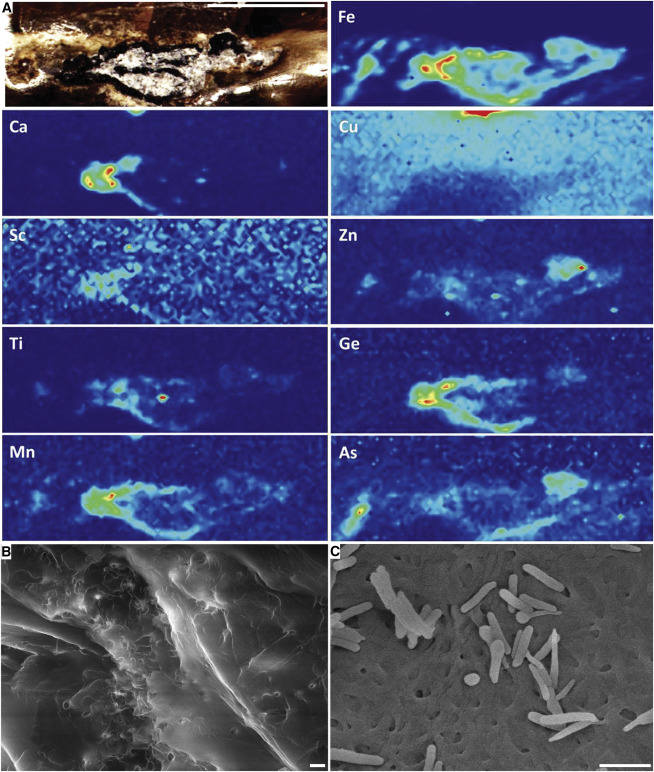

SR μ-XFI Maps and Scanning Electron Micrographs of DIP-V-15103

(A) Elemental maps and region of interest (ROI) image for exposed soft tissue preservation in DIP-V-15103; black carbon film surrounds clay minerals infilling void between vertebrae or partially replacing them; milky amber related to decay surrounds vertebrae and plumage (ROI prior to clay flake removal is better visible in Figure S3H).

(B) Patchy keratin preservation with traces of fibrous structure in DIP-V-15103 ventral feather.

(C) Fibrous keratin sheets and isolated melanosomes from barb of modern Indian peafowl (Pavo cristatus; Galliformes).Scale bars, 2 mm in (A) and 1 μm in (B) and (C). See also Figure S3.

The study’s first author Lida Xing from the China University of Geosciences in Beijing discovered the remarkable specimen at an amber market in Myitkyina, Myanmar in 2015.

The amber piece was originally seen as some kind of plant inclusion and destined to become a curiosity or piece of jewellery, but Xing recognized its potential scientific importance and suggested the Dexu Institute of Palaeontology buy the specimen.

The researchers say the specimen represents the feathered tail of a theropod preserved in mid-Cretaceous amber about 99 million years ago. While it was initially difficult to make out details of the amber inclusion, Xing and his colleagues relied on CT scanning and microscopic observations to get a closer look.

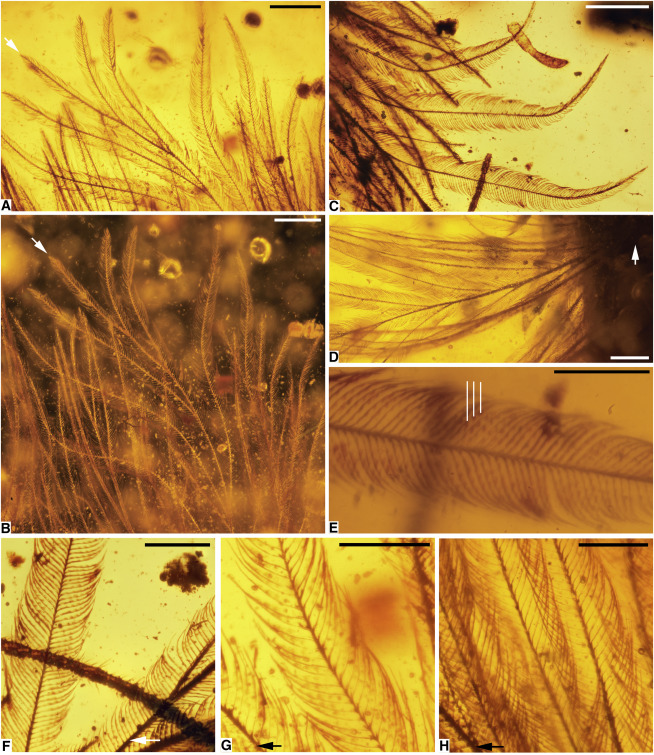

Photomicrographs of DIP-V-15103 Plumage

(A) Pale ventral feather in transmitted light (arrow indicates rachis apex).

(B) Dark-field image of (A), highlighting structure and visible color.

(C) Dark dorsal feather in transmitted light, apex toward bottom of image.

(D) Base of ventral feather (arrow) with weakly developed rachis.

(E) Pigment distribution and microstructure of barbules in (C), with white lines pointing to pigmented regions of barbules.

(F–H) Barbule structure variation and pigmentation, among barbs, and ‘rachis’ with rachidial barbules (near arrows); images from apical, mid-feather, and basal positions respectively.

Scale bars, 1 mm in (A), 0.5 mm in (B)–(E), and 0.25 mm in (F)–(H). See also Figure S4.

The feathers suggest the tail had a chestnut-brown upper surface and a pale or white underside. The specimen also offers insight into feather evolution. The feathers lack a well-developed central shaft or rachis. Their structure suggests that the two finest tiers of branching in modern feathers, known as barbs and barbules, arose before a rachis formed.

Professor Mike Benton from the School of Earth Sciences at the University of Bristol, added: “It’s amazing to see all the details of a dinosaur tail — the bones, flesh, skin, and feathers — and to imagine how this little fellow got his tail caught in the resin, and then presumably died because he could not wrestle free.

“There’s no thought that dinosaurs could shed their tails, as some lizards do today.”

![DIP-V-15103 Structural Overview and Feather Evolutionary-Developmental Model Fit (A and B) Overview of largest and most planar feather on tail (dorsal series, anterior end), with matching interpretive diagram of barbs and barbules. Barbules are omitted on upper side and on one barb section (near black arrow) to show rachidial barbules and structure; white arrow indicates follicle. (C) Evolutionary-developmental model and placement of new amber specimen. Brown denotes calamus, blue denotes barb ramus, red denotes barbule, and purple denotes rachis [as in 5, 12]. Scale bars, 1 mm in (A) and (B).](http://www.worldfossilsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/151209183454_1_540x360-8.jpg)

DIP-V-15103 Structural Overview and Feather Evolutionary-Developmental Model Fit

(A and B) Overview of largest and most planar feather on tail (dorsal series, anterior end), with matching interpretive diagram of barbs and barbules. Barbules are omitted on upper side and on one barb section (near black arrow) to show rachidial barbules and structure; white arrow indicates follicle.

(C) Evolutionary-developmental model and placement of new amber specimen. Brown denotes calamus, blue denotes barb ramus, red denotes barbule, and purple denotes rachis [as in 5, 12].

Scale bars, 1 mm in (A) and (B).

“This is a new source of information that is worth researching with intensity, and protecting as a fossil resource.”

The researchers say they are now “eager to see how additional finds from this region will reshape our understanding of plumage and soft tissues in dinosaurs and other vertebrates.”

Citation:Lida Xing, Ryan C. McKellar, Xing Xu, Gang Li, Ming Bai, W. Scott Persons IV, Tetsuto Miyashita, Michael J. Benton, Jianping Zhang, Alexander P. Wolfe, Qiru Yi, Kuowei Tseng, Hao Ran, Philip J. Currie. A Feathered Dinosaur Tail with Primitive Plumage Trapped in Mid-Cretaceous Amber. Current Biology, 2016; DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.10.008

Key: WFS,World Fossil Society,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

December 13th, 2016

December 13th, 2016  Riffin

Riffin  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: