@WFS,World Fossil Society,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

The giant Tyrannosaurus rex pulverized bones by biting down with forces equaling the weight of three small cars while simultaneously generating world record tooth pressures, according to a new study by a Florida State University-Oklahoma State University research team.

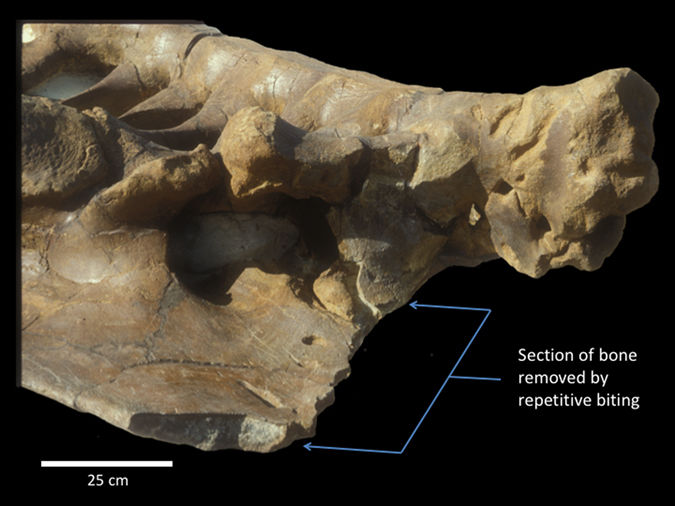

Left ilium of Triceratops sp. (MOR 799) in ventrolateral view with ~80 bite marks attributed to Tyrannosaurus rex. A large portion (~17%) of the iliac crest was removed (bracketed) by repetitive, localized biting.

In a study published today in Scientific Reports, Florida State University Professor of Biological Science Gregory Erickson and Paul Gignac, assistant professor of Anatomy and Vertebrate Paleontology at Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences, explain how T. rex could pulverize bones — a capacity known as extreme osteophagy that is typically seen in living carnivorous mammals such as wolves and hyenas, but not reptiles whose teeth do not allow for chewing up bones.

@WFS,World Fossil Society,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

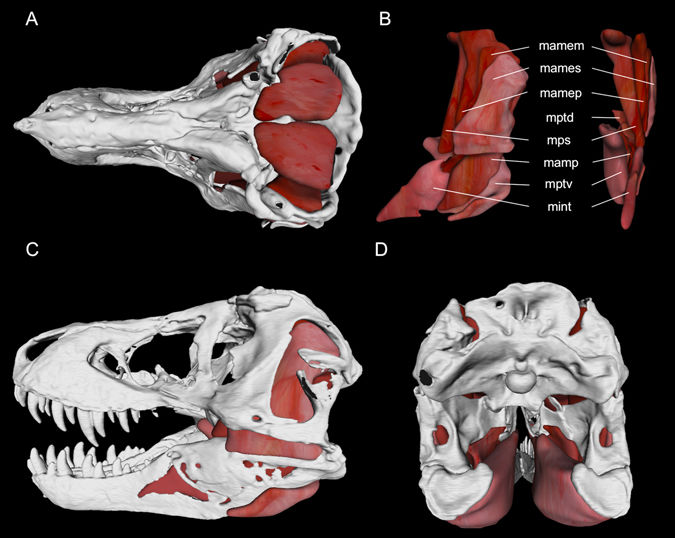

Jaw adductor muscle model for Tyrannosaurus rex (BHI 3033) in (A) dorsal, (C) left lateral, and (D) posterior views. Muscles in anatomical position are figured in (B) (lateral view is on left; anterior view is on right), textures and shades based on Alligator mississippiensis 32. Abbreviations: mamem, Musculus adductor mandibulae externus medialis; mames, M. adductor mandibulae externus superficialis; mamep, M. adductor mandibulae externus profundus; mptd, M. pterygoideus dorsalis; mps, M. pseudotemporalis complex; mamp, M. adductor mandibulae posterior; mptv, M. pterygoideus ventralis; mint, M. intramandibularis.

Erickson and Gignac found that this prehistoric reptile could chow down with nearly 8,000 pounds of force, which is more than two times greater than the bite force of the largest living crocodiles — today’s bite force champions. At the same time, their long, conical teeth generated an astounding 431,000 pounds per square inch of bone-failing tooth pressures.

This allowed T. rex to drive open cracks in bone during repetitive, mammal-like biting and produce high-pressure fracture arcades, leading to a catastrophic explosion of some bones.

“It was this bone-crunching acumen that helped T. rex to more fully exploit the carcasses of large horned-dinosaurs and duck-billed hadrosaurids whose bones, rich in mineral salts and marrow, were unavailable to smaller, less equipped carnivorous dinosaurs,” Gignac said.

@WFS,World Fossil Society,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

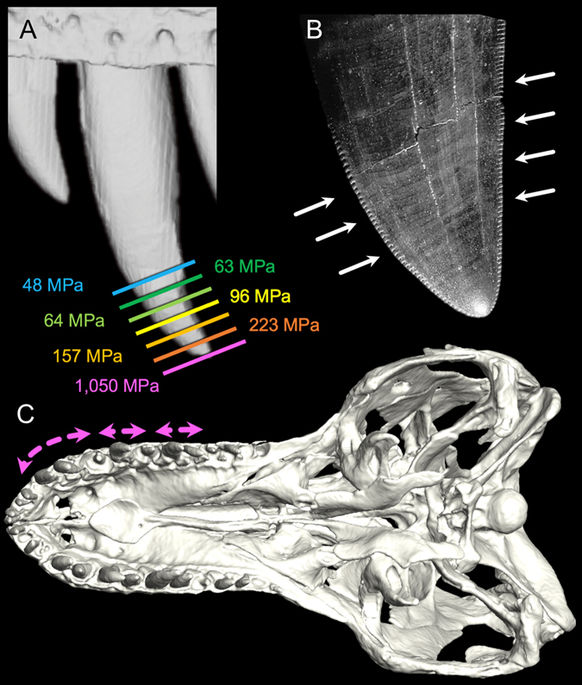

Tyrannosaurus rex dental functional morphology. (A) Exemplar tooth pressures along the distal 37 mm of the left M5 of BHI 3033 (warmer colours indicate higher pressures), illustrating bone-penetrating shear stresses (>65 MPa4, 39) for almost 25 mm of indentation depth. (B) Mesial and distal facing carinae (white arrows) helped direct pathways of bone fracture towards adjacent maxillary teeth (C) (ventral view of BHI 3033) that were also engaged during indentation, illustrating how the most procumbent maxillary tooth crowns collectively form a fracture arcade (pink arrows) due to pressures generated when biting. (Figure element in (A) derived from digital scan by Virtual Surfaces, Inc).

The researchers built on their extensive experience testing and modeling how the musculature of living crocodilians, which are close relatives of dinosaurs, contribute to bite forces. They then compared the results with birds, which are modern-day dinosaurs, and generated a model for T. rex.

From their work on crocodilians, they realized that high bite forces were only part of the story. To understand how the giant dinosaur consumed bone, Erickson and Gignac also needed to understand how those forces were transmitted through the teeth, a measurement they call tooth pressure.

“Having high bite force doesn’t necessarily mean an animal can puncture hide or pulverize bone, tooth pressure is the biomechanically more relevant parameter,” Erickson said. “It is like assuming a 600 horsepower engine guarantees speed. In a Ferrari, sure, but not for a dump truck.”

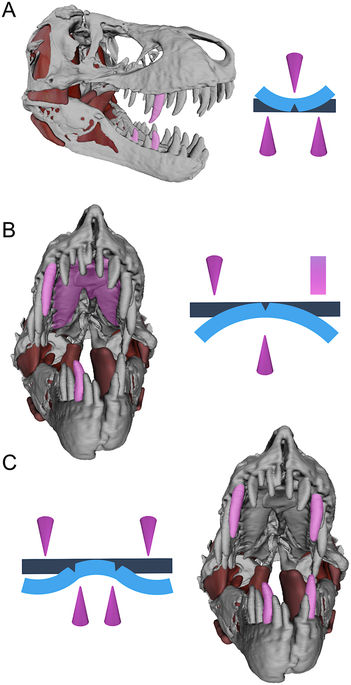

Jaw models of Tyrannosaurus rex paired with idealized beam diagrams, illustrating three- (A) (lateral view), (B) (anterior view) and four-point ((C), anterior view) loading configurations that allowed T. rex to promote failure stresses and fracture rigid structures (e.g., bone) without the aid of occluding dentitions. Teeth (cones) and the osseus palate, composed of the right and left maxillae and an anterior expansion of the vomer (rectangle), are shown as contact points in pink; original beam shapes are dark blue; and idealized plastic deformations (exaggerated) are light blue.

In current day, well-known bone crunchers like spotted hyenas and gray wolves have occluding teeth that are used to finely fragment long bones for access to the marrow inside — a hallmark feature of mammalian osteophagy. Tyrannosaurus rex appears to be unique among reptiles for achieving this mammal-like ability but without specialized, occluding dentition.

The new study is one of several by the authors and their colleagues that now show how sophisticated feeding abilities, most like those of modern mammals and their immediate ancestors, actually first appeared in reptiles during the Age of the Dinosaurs.

@WFS,World Fossil Society,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

Citation:Paul M. Gignac, Gregory M. Erickson. The Biomechanics Behind Extreme Osteophagy in Tyrannosaurus rex. Scientific Reports, 2017; 7 (1) DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-02161-w

May 19th, 2017

May 19th, 2017  Riffin

Riffin  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: