@WFS,World Fossil Society,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

An exceptionally-preserved fossil from the Alps in eastern Switzerland has revealed the best look so far at an armoured reptile from the Middle Triassic named Eusaurosphargis dalsassoi. The fossil is extremely rare in that it contains the animal’s complete skeleton, giving an Anglo-Swiss research team a very clear idea of its detailed anatomy and probable lifestyle for the first time, according to a paper published in Scientific Reports today.

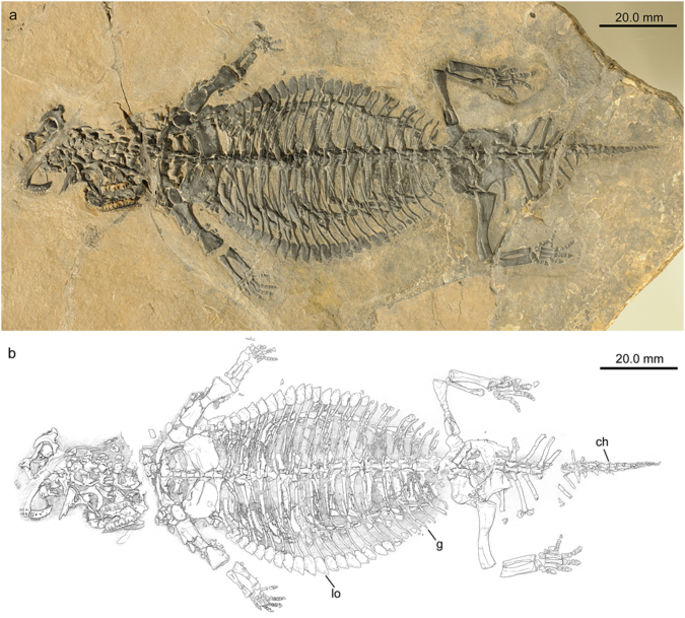

Eusaurosphargis dalsassoi (PIMUZ A/III 4380) in ventral view. (a) Photograph. (b) Interpretative drawing of skeleton. Abbreviations used in the figure are chevron (ch), gastralia (g), and lateral osteoderm (lo).

At just 20 cm long, the specimen represents the remains of a juvenile. Yet large portions of its body were covered in armour plates, with a distinctively spiky row around each flank, protecting the animal from predators. Today’s girdled lizards, found in Africa, have independently evolved a very similar appearance even though they are not closely related to Eusaurosphargis.

The new fossil, found in the Prosanto Formation at Ducanfurgga, south of Davos in Switzerland, is not the first material of Eusaurosphargis to be discovered. The species was originally described in 2003 based on a partially complete and totally disarticulated specimen from Italy. This was found alongside fossils of fishes and marine reptiles, leading scientists to believe that Eusaurosphargis was an aquatic animal.

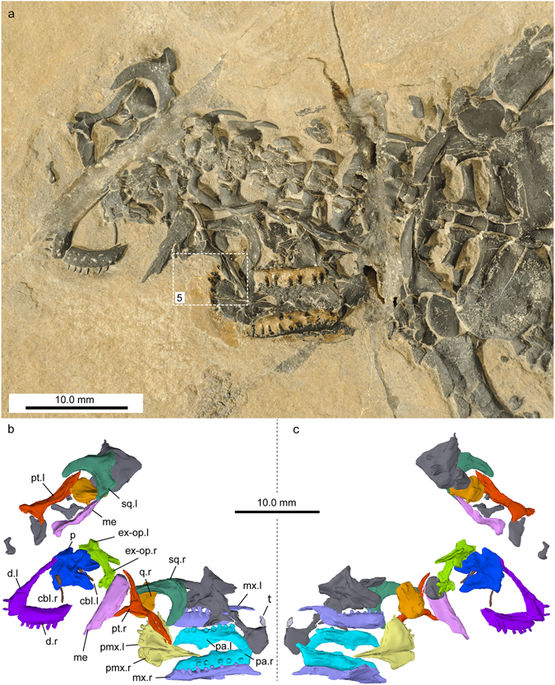

Skull and lower jaw elements of Eusaurosphargis dalsassoi (PIMUZ A/III 4380) in ventral view. (a) Photograph. White rectangle indicates section of skull shown in Fig. 5. (b,c) Virtual reconstruction of the cranial bones in ventral (b) and dorsal (c) view. Unidentified bones are shown in dark grey. Note that when possible the left (.l) and right (.r) side is indicated for the identified elements. Abbreviations used in the figure are ceratobranchial I (cbI), dentary (d), exoccipital-opisthotic (ex-op), mandible element (me), maxilla (mx), parietals (p), palatine (pa), premaxilla (pmx), pterygoid (pt), quadrate (q), squamosal (sq), and tooth (t).

However, the detail preserved in the new specimen shows a skeleton without a streamlined body outline and no modification of the arms, legs or tail for swimming. This suggests that the reptile was in fact most probably adapted to live, at least mostly, on land, even though all of its closest evolutionary relatives lived in the water.

“Until this new discovery we thought that Eusaurosphargis was aquatic, so we were astonished to discover that the skeleton actually shows adaptations to life on the land,” says Dr James Neenan, research fellow at Oxford University Museum of Natural History and co-author of the new paper about Eusaurosphargis dalsassoi. “We think this particular animal must have washed into the sea from somewhere like a beach, where it sank to the sea floor, was buried and finally fossilised.”

Zeugopodial and autopodial bones of the forelimb of Eusaurosphargis dalsassoi (PIMUZ A/III 4380). (a) Photograph. (b) Photograph overlain by interpretative drawing. Abbreviations used in the figure are entepicondyle (ent), entepicondylar foramen (entf), humerus (hu), intermedium (im), lateral osteoderm (lo), metacarpal (mc), osteoderm (o), radius (ra), ulna (ul), ulnare (uln), and digits 1 to 5 (I–V).

The findings from the research team are published in Scientific Reports as ‘A new, exceptionally preserved juvenile specimen of Eusaurosphargis dalsassoi (Diapsida) and implications for Mesozoic marine diapsid phylogeny’.

![]() More information: ‘A new, exceptionally preserved juvenile specimen of Eusaurosphargis dalsassoi (Diapsida) and implications for Mesozoic marine diapsid phylogeny’ Scientific Reports (2017). www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-04514-x , DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-04514-x

More information: ‘A new, exceptionally preserved juvenile specimen of Eusaurosphargis dalsassoi (Diapsida) and implications for Mesozoic marine diapsid phylogeny’ Scientific Reports (2017). www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-04514-x , DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-04514-x

@WFS,World Fossil Society,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

June 30th, 2017

June 30th, 2017  Riffin

Riffin  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: