Research led by scientists at the American Museum of Natural History shows that ammonites-an extinct type of shelled mollusk that’s closely related to modern-day nautiluses and squids-made homes in the unique environments surrounding methane seeps in the seaway that once covered America’s Great Plains. The findings, published online this week in the journalGeology, provide new insights into the mode of life and habitat of these ancient animals.

Geologic formations in parts of South Dakota, Wyoming, and Montana formed as sediments were deposited in the Western Interior Seaway-a broad expanse of water that split North America into two land masses-during the Late Cretaceous, 80 to 65 million years ago. These formations are popular destinations for paleontologists looking for everything from fossilized dinosaur bones to ancient clam shells. In the last few years, groups of researchers have honed in on giant mounds of fossilized material in these areas where, many millions of years ago, methane-rich fluids migrated through the sediments onto the sea floor.

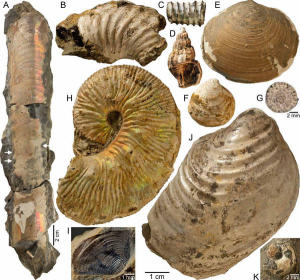

“We’ve found that these methane seeps are little oases on the sea floor, little self-perpetuating ecosystems,” said Neil Landman, lead author of the Geology paper and a curator in the Division of Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History. “Thousands of these seeps have been found in the Western Interior Seaway, most containing a very rich fauna of bivalves, sponges, corals, fish, crinoids, and, as we’ve recently documented, ammonites.”

In the Black Hills region of South Dakota, Landman and researchers from Stony Brook University’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, the Black Hills Museum of Natural History, Brooklyn College, the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, and the University of South Florida are investigating a 74-million-year-old seep with extremely well-preserved fossils.

“Most seeps have eroded significantly over the last 70 million years,” Landman said. “But this seep is part of a cliff whose face recently slumped off. As the cliff fell away, it revealed beautiful, glistening shells of all sorts of marine life.”

Studying these well-preserved shells, the researchers tried to determine the role of ammonites in the unique seep ecosystem. By analyzing the abundance of isotopes (alternative forms) of carbon, oxygen, and strontium, the group made a surprising discovery. The ammonites at the seep, once thought to be just passersby, had spent their whole lives there.

“Ammonites are generally considered mobile animals, freely coming and going” Landman said. “That’s a characteristic that really distinguishes them from other mollusks that sit on the sea floor. But to my astonishment, our analysis showed that these ammonites, while mobile, seemed to have lived their whole life at a seep, forming an integral part of an interwoven community.”

The seeps, which the researchers confirmed through oxygen isotope analysis to be “cold” (about 27 degrees Celsius, 80 degrees Fahrenheit), also likely attracted large clusters of plankton Ð the ammonites’ preferred prey.

With these findings in mind, the researchers think that the methane seeps probably played a role in the evolution of ammonites and other faunal elements in the Western Interior Seaway. The seeps might have formed small mounds that rose above the oxygen-poor sea floor, creating mini oases in a less-hospitable setting. This could be a reason why ammonites were able to inhabit the seaway over millions of years in spite of occasional environmental disturbances.

“If a nearby volcano erupted and ash covered part of the basin, it would have decimated ammonites in that area,” Landman said. “But if these communities of seep ammonites survived, they could have repopulated the rest of the seaway. These habitats might have been semi-permanent, self-sustaining sites that acted as hedges against extinction.”

Isotope analysis of strontium also revealed an interesting geologic finding: seep fluids coming into the seaway were in contact with granite, meaning that they traveled from deep in the Earth. This suggests that the Black Hills, a small mountain range in the area, already were beginning to form in the Late Cretaceous, even though the uplift wasn’t fully complete until many millions of years later.

This research was supported by the American Museum of Natural History and a National Science Foundation Research Experience for Undergraduates grant for two students from Brooklyn College to participate in the field work.

August 4th, 2012

August 4th, 2012  riffin

riffin

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: