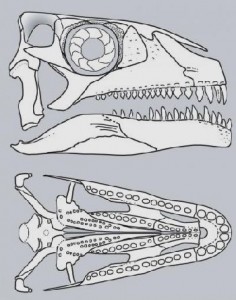

Azendohsaurus just shed its dinosaur affiliation. A careful new analysis of A. madagaskarensis—this time based on the entire skull rather than on just teeth and jaws—aligns this 230-million-year-old animal with a different and very early branch on the reptile evolutionary tree. Many aspects of Azendohsaurus are far more primitive than previously assumed, which in turn means that its plant-eating adaptations, similar to those found some early dinosaurs, were developed independently. The new analysis is published in the journal Palaeontology.

“Even though this extraordinary ancient reptile looks similar to some plant-eating dinosaurs in some features of the skull and dentition, it is in fact only distantly related to dinosaurs,” says John J. Flynn, curator in the Division of Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History. “With more complete material, we re-assessed features like the down-turned jaw and leaf-shaped teeth found in A. madagaskarensis as convergent with some herbivorous dinosaurs.”

The fossil is a member of Archosauromorpha, a group that includes birds and crocodilians but not lizards, snakes, or turtles. The type specimen of the genus Azendohsaurus was a fragmentary set of teeth and jaws found in 1972 near (and named for) a village in Morocco’s Atlas Mountains. The fossils on which the current research paper is based was discovered in the late 1990s in southwestern Madagascar. Named A. madagaskarensis, this specimen was uncovered by a team of U.S. and Malagasy paleontologists in a “red bed” that includes multiple individuals that probably perished together. This species was initially published as an early dinosaur in Science over a decade ago, but the completeness of the more recently unearthed and studied fossils has provided the first complete glimpse of what this animal looked like and was related to. A. madagaskarensis was not a dinosaur.

“Now there are many more cases of herbivorous archosaurs,” says Andr� Wyss, professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “We are rethinking the evolution of diet and feeding strategies, as well as the broader evolution of the group.”

“This is the way science works,” says Flynn, commenting on the reinterpretation of the fossils. “As we found and analyzed more material, it made us realize that this was a much more primitive animal and the dinosaur-like features were really the product of convergent evolution.”

Wyss adds, “In many ways Azendohsaurus ends up being a much more fantastic animal than if it simply represented a generic early dinosaur.”

In addition to Flynn and Wyss, authors include Sterling Nesbitt, a former graduated student affiliated with the Museum and Columbia University; J. Michael Parrish, San Jose State University in California; and Lovasoa Ranivoharimanana, Universit� d�Antananarivo in Madagascar. This research was funded by the National Geographic Society, The Field Museum, American Museum of Natural History, the University of California Santa Barbara, and Worldwide Fund for Nature, Madagascar.

August 20th, 2012

August 20th, 2012  riffin

riffin

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: