The seas may be rising due to climate change, but most of the seafloor is also dropping as part of the natural dynamics of Earth’s crust. The question that has dogged scientists for decades, however, is why hasn’t the ocean bottom sunk faster? An exhaustive analysis of the Pacific Ocean seabed may provide at least part of the answer—though experts think important questions remain.

Earth’s crust is like an ice field floating atop the ocean. As tectonic plates move away from each other, the underlying mantle wells up between them. This process builds underwater mountain ranges, such as the central ridges of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The mantle also heats the plates near this upwelling, making them more buoyant—and thus raising the seafloor. As the new crust cools, it sinks under its own weight—a process called subsidence—so the seafloor should be deeper the farther it is from a mid-ocean ridge.

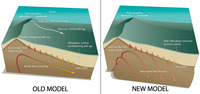

But that’s not what scientists have found. In the oldest parts of the seafloor, which are also the parts farthest away from the mid-ocean ridges, the ocean bottom tends to be considerably shallower than expected—in some cases hundreds of meters shallower. What has been holding it up?

Out with the old. New findings show a more dynamic role for Earth’s mantle in shoring up the sea bottom.

On the other hand, geophysicist Dave Stegman of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, California, calls the results of the paper “exciting and profound.” If confirmed, he says, the findings mean that we now understand “a very fundamental aspect of tectonics and the evolution of the Earth.” The findings might even explain the puzzling curve in the migration of the Hawaiian Islands chain over millions of years, he says, because their motion might have been governed by mantle processes instead of tectonics.

Geophysicist Seth Stein of Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, predicts that the new model will catch on if it can reliably explain certain aspects of seafloor dynamics, such as whether the seafloor flattens in the Atlantic and Indian oceans in the same way as it does in the Pacific. Otherwise, he says, the standard models will probably persist because “they still do a reasonable job in predicting ocean depth, including the flattening.”

August 16th, 2012

August 16th, 2012  riffin

riffin  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: