The collapse of honeybee colonies across North America is focusing attention on the honeybees’ vital role in the survival of agricultural crops, and a new study by University of Florida and Indiana University Southeast researchers shows insect pollinators have likely played a key role in the evolution and success of flowering plants for nearly 100 million years.

The origins of when flowers managed to harness insects’ pollinating power has long been murky. But the new study, published online this week on the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Web site and appearing in its Dec. 24 print edition, is the first to pinpoint a 96-million-year-old timeframe for a turning point in the evolution of basal angiosperm groups, or early flowering plants, by demonstrating they are predominantly insect-pollinated.

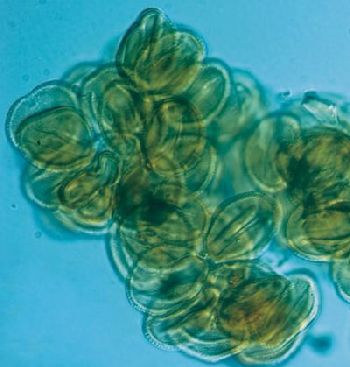

This 96-million-year-old fossilized angiosperm pollen clump of Phimopollenites striolata was extracted by careful processing of sediment from three sites in Minnesota’s Dakota Formation. Florida Museum of Natural History researchers found about 40 separate clumps in the pollen samples used for a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Dec. 24 print edition. Each individual grain within the clump in this image measures approximately 14-by-19 microns. Clumping is generally found only in animal-pollinated flowering plants.

“Our study of clumping pollen shows that insect pollinators most likely have always played a large role in the evolution of flowering plants,” said David Dilcher, a graduate research professor of paleobotany at the Florida Museum of Natural History. “It was true 96 million years ago and we are seeing it today with the potential threat to our agricultural crops because of the collapse of the honeybee colonies. The insect pollinators provide for more efficient and effective pollination of flowering plants.”

The study provides strong evidence for the widely accepted hypothesis that insects drove the massive adaptive radiation of early flowering plants when they rapidly diversified and expanded to exploit new terrestrial niches. Land plants first appear in the fossil record about 425 million years ago, but flowering plants didn’t appear until about 125 million years ago in the Early Cretaceous period.

The study also is the first to describe the biological structure of pollen clumping in the early Late Cretaceous, which holds clues about the types of pollinators with which they were coevolving, said lead author Shusheng Hu, who started the study while at the Florida Museum but is currently at Indiana University Southeast. Hu said previous scientists found examples of early clumped pollen from a slightly earlier time period but these were interpreted as immature parts of anther from a flower, or dismissed as insect packaging activity or fecal pellets.

“We really had to jump out of the box and think in a new way on these widespread pollen clumps,” said Hu, who completed the research in 2006 as part of his UF doctoral work.

Today, flowers specialized for insect pollination disperse clumps of five to 100 pollen grains. Clumped grains are comparatively larger and have more surface relief than wind- or water-dispersed pollen, which tend to be single, smaller and smoother.

“These clumps represent an amazing new strategy in the evolution of flowering plants,” Dilcher said. “For me, the excitement here lies in the early times of these fossil flowers, when angiosperms were making these huge evolutionary steps. What we found with the fossil pollen clumps folds nicely into what has been suggested by molecular biologists that those plants that are basal in angiosperm evolutionary relationships seem to have been dominated by insect pollination.”

The nine species of fossil pollen clumps, combined with known structural changes occurring in flowering plants at this time, led the researchers to suggest that insect pollination was well established by the early Late Cretaceous – only a few million years before the explosion in diversity and distribution of flowering plant families. Known structural changes include early prototypes of stamen and anther, plant organs which lift pollen up and away from the plant, positioning the plants’ genetic material to be passed off to visiting insects.

The researchers sampled pollen from three sites in Minnesota’s Dakota Formation, which represents a time period when a shallow seaway covered North America’s interior.

Co-author David Jarzen, a Florida Museum pollen scientist, refined existing pollen processing techniques for extracting intact fossil pollen from the calcareous Minnesota limestone and silicate mudstone rock matrix. Co-author David Taylor, a botanist from Indiana University Southeast contributed a statistical analysis of pollination methods among living and early plants.

A Smithsonian Institution paleobiologist, Conrad Labandeira, who specializes in insect-plant associations, and who is unassociated with the study, said that the authors’ ability to demonstrate pollen clumping in basal angiosperms adds one more piece to the puzzle of several pollination types established in the mid-Cretaceous.

“These data are very comparable with parallel data such as flower structure, pollen structure, and insect mouthpart morphology, that now documents a wide variety of pollination types that occurred before the Cenomanian,” Labandeira said.

Note: This story has been adapted from a news in 2007 release issued by the University of Florida

April 13th, 2013

April 13th, 2013  Riffin

Riffin  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: