Drill holes made by predators in prey shells are widely considered to be the most unambiguous bodies of evidence of predator-prey interactions in the fossil record. However, recognition of traces of predatory origin from those formed by abiotic factors still waits for a rigorous evaluation as a prerequisite to ascertain predation intensity through geologic time and to test macroevolutionary patterns. New experimental data from tumbling various extant shells demonstrate that abrasion may leave holes strongly resembling the traces produced by drilling predators. They typically represent singular, circular to oval penetrations perpendicular to the shell surface. These data provide an alternative explanation to the drilling predation hypothesis for the origin of holes recorded in fossil shells. Although various non-morphological criteria (evaluation of holes for non-random distribution) and morphometric studies (quantification of the drill hole shape) have been employed to separate biological from abiotic traces, these are probably insufficient to exclude abrasion artifacts, consequently leading to overestimate predation intensity. As a result, from now on, we must adopt more rigorous criteria to appropriately distinguish abrasion artifacts from drill holes, such as microstructural identification of micro-rasping traces.

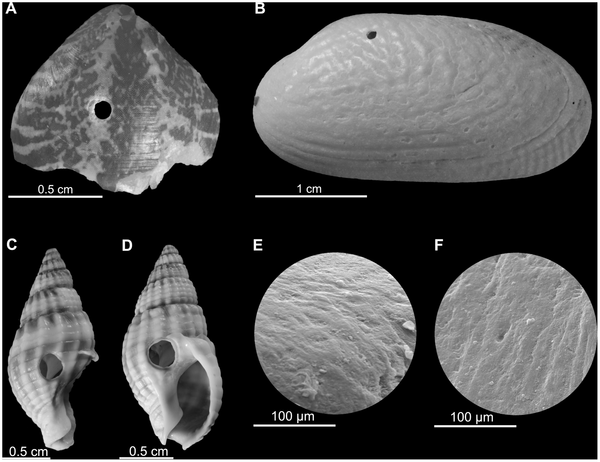

Holes generated by tumbling experiments on various shells.

(A) Brachiopod shell (Frenulina sanguinolenta) (GIUS 12-3616/Fs1) after 4 hours of tumbling. (B) Unionidae bivalve shell (GIUS 12-3616/U1) after 1 hour of tumbling. (C–D) Gastropod shells (Nassarius sp.) (GIUS 12-3616/N1-2) after 2 hours of tumbling. (E–F) Close up of hole margins in Nassarius sp.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058528.g001

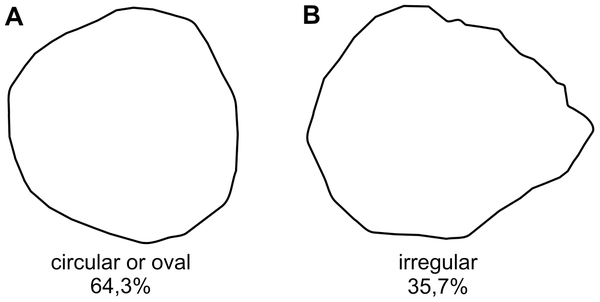

Two morphotypes of the inner outlines of holes and their frequency distribution (drawings by camera lucida).

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058528.g002

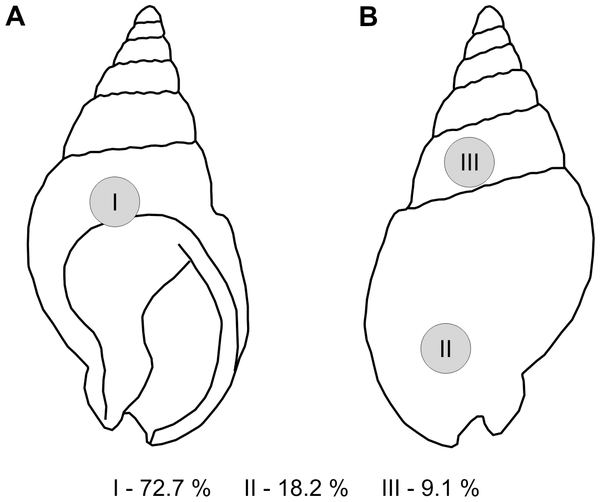

Frequency distribution of holes in Nassarius sp.

(A) Apertural view. (B) Abapertural view.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058528.g005

Citation: Gorzelak P, Salamon MA, Trzęsiok D, Niedźwiedzki R (2013) Drill Holes and Predation Traces versus Abrasion-Induced Artifacts Revealed by Tumbling Experiments. PLoS ONE 8(3): e58528. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058528

Editor: David Caramelli, University of Florence, Italy

November 24th, 2013

November 24th, 2013  Riffin

Riffin  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: