For centuries, geologists have recognized that the rocks that line riverbeds tend to be smaller and rounder further downstream. But these experts have not agreed on the reason these patterns exist. Abrasion causes rocks to grind down and become rounder as they are transported down the river. Does this grinding reduce the size of rocks significantly, or is it that smaller rocks are simply more easily transported downstream?

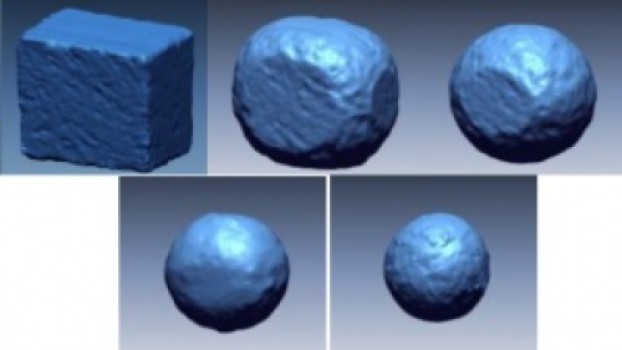

The team devised a mathematical model to show that a rock becomes round (top row) and then shrinks (bottom row).

Credit: University of Pennsylvania

A new study by the University of Pennsylvania’s Douglas Jerolmack, working with mathematicians at Budapest University of Technology and Economics, has arrived at a resolution to this puzzle. Contrary to what many geologists have believed, the team’s model suggests that abrasion plays a key role in upholding these patterns, but it does so in a distinctive, two-phase process. First, abrasion makes a rock round. Then, only when the rock is smooth, does abrasion act to make it smaller in diameter.

“It was a rather remarkable and simple result that helps to solve an outstanding problem in geology,” Jerolmack said.

Not only does the model help explain the process of erosion and sediment travel in rivers, but it could also help geologists answer questions about a river’s history, such as how long it has flowed. Such information is particularly interesting in light of the rounded pebbles recently discovered on Mars — seemingly evidence of a lengthy history of flowing rivers on its surface.

Jerolmack, an associate professor in Penn’s Department of Earth and Environmental Science, lent a geologist’s perspective to the Hungarian research team, composed of Gábor Domokos, András Sipos and Ákos Török.

Their work is to be published in the journal PLOS ONE.

Prior to this study, most geologists did not believe that abrasion could be the dominant force responsible for the gradient of rock size in rivers because experimental evidence pointed to it being too slow a process to explain observed patterns. Instead, they pointed to size-selective transport as the explanation for the pattern: small rocks being more easily transported downstream.

The Budapest University researchers, however, approached the question of how rocks become round purely as a geometrical problem, not a geological one. The mathematical model they conceived formalizes the notion, which may seem intuitive, that sharp corners and protruding parts of a rock will wear down faster than parts that protrude less.

The equation they conceived relates the erosion rate of any surface of a pebble with the curvature of the pebble. According to their model, areas of high curvature erode quickly, and areas of zero or negative curvature do not erode at all.

The math that undergirds their explanation for how pebbles become smooth is similar to the equation that explains how heat flows in a given space; both are problems of diffusion.

“Our paper explains the geometrical evolution of pebble shapes,” said Domokos, “and associated geological observations, based on an analogy with an equation that describes the variation of temperature in space and time. In our analogy, temperature corresponds to geometric (or Gaussian) curvature. The mathematical root of our paper is the pioneering work of mathematician Richard Hamilton on the Gauss curvature flow.”

From this geometric model comes the novel prediction that abrasion of rocks should occur in two phases. In the first phase, protruding areas are worn down without any change in the diameter of the pebble. In the second phase, the pebble begins to shrink.

“If you start out with a rock shaped like a cube, for example,” Jerolmack said, “and start banging it into a wall, the model predicts that under almost any scenario that the rock will erode to a sphere with a diameter exactly as long as one of the cube’s sides. Only once it becomes a perfect sphere will it then begin to reduce in diameter.”

The research team also completed an experiment to confirm their model, taking a cube of sandstone and placing it in a tumbler and monitoring its shape as it eroded.

“The shape evolved exactly as the model predicted,” Jerolmack said.

The finding has a number of implications for geologic questions. One is that rocks can lose a significant amount of their mass before their diameter starts to shrink. Yet geologists typically measure river rock size by diameter, not weight.

“If all we’re doing in the field is measuring diameter, then we’re missing the whole part of shape evolution that can occur without any change in diameter,” Jerolmack said. “We’re underestimating the importance of abrasion because we’re not measuring enough about the pebble.”

As a result, Jerolmack noted that geologists may also have been underestimating how much sand and silt arises because of abrasion, the material ground off of the rocks that travel downstream.

“The fine particles that are produced by abrasion are the things that go into producing the floodplain downstream in the river; it’s the sand that gets deposited on the beach; it’s the mud that gets deposited in the estuary,” he said.

With this new understanding of how the process of abrasion proceeds, researchers can address other questions about river flow — both here on Earth and elsewhere, such as on Mars, where NASA’s rover Curiosity recently discovered rounded pebbles indicative of ancient river flow.

“If you pluck a pebble out of a riverbed,” Jerolmack said, “a question you might like to answer, how far has this pebble traveled? And how long has it taken to reach this place?”

Such questions are among those that Jerolmack and colleagues are now asking.

“If we know something about a rock’s initial shape, we can model how it went from its initial shape to the current one,” he said. “On Mars, we’ve seen evidence of river channels, but what everyone wants to know is, was Mars warm and wet for a long time, such that you could have had life? If I can say how long it took for this pebble to grind down to this shape, I can put a constraint on how long Mars needed to have stable liquid water on the surface.”

February 24th, 2014

February 24th, 2014  Riffin

Riffin  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: