About 112 million years ago, a long-necked sauropod dinosaur traversed some intertidal flats near what is now Glen Rose, Texas. Coming after it — perhaps hours or days later, or perhaps hot on its tail in a dinosaur chase scene — a meat-eating theropod followed, overlaying some of the sauropod’s footprints with its own.

This snippet of the Cretaceous ended up frozen in rock, and paleontologists discovered the prints as early as 1917. But an excavation in 1940 led to a third of the trackway vanishing. Now, researchers have reconstructed the entire trackway, all 148 feet (45 meters) of it, using old photography and new technology.

“It’s great to get so many stride lengths, so many depths and impressions,” said study researcher Peter Falkingham, a research fellow at Royal Veterinary College in London. “There’s all this data you can get from an animal moving over quite a long distance.” [Video: ‘Fly’ Through the Cretaceous Dinosaur Chase]

Lost footprints

The dinosaur footprints come from a larger site full of tracks called the Paluxy River Trackway. The sauropod and theropod prints comprise one of the most famous sequences from the site. In 1940, fossil collector Roland T. Bird excavated the tracks. A third of the sequence went to the American Museum of Natural History in New York; another third went to the Texas Memorial Museum, and a final third was lost.

“It’s entirely possible that there are some parts of it in a garage somewhere,” Falkingham told Live Science. Portions of the fossil could have been sent to other institutions and lost, or perhaps left at the site and eroded away by the river, he said.

Bird did carefully document the site, however. Falkingham and his colleagues analyzed Bird’s 70-year-old photos with a technique called photogrammetry, which allows researchers to determine where the camera was when the photo was taken. By melding views from different camera angles, the team created a digital model of the trackway, with three-dimensional depth, just as the viewpoint from two different eyes gives people depth perception.

Tracks reconstructed

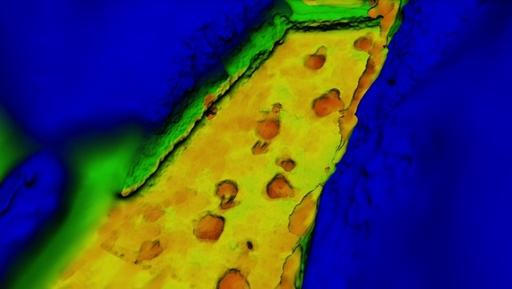

The resulting image is fuzzy at the north end, where the photographs were less comprehensive, but detailed enough that the dinosaurs’ toe prints can be seen at the south end of the trackway.

The 3D reconstruction has already solved one long-running mystery. When Bird excavated the tracks, he drew two maps of the prints, one showing a fairly straight path, and the other with a slight curve to the left. By overlaying the reconstruction with the maps, Falkingham and his colleagues showed the left-curving map was the more accurate one.

A 3D reconstruction of a dinosaur trackway from Texas shows a sauropod followed by a theropod — though it’s not clear that the theropod was really right on the first dinosaur’s tail.

“We’ll be pulling this into a larger study of the tracks in the area,” Falkingham said. The 3D model allows researchers to study depth and weight distribution for each of the dinosaurs, which helps determine how the animals walked and how fast they were going.

The researchers report their findings in the journal PLOS ONE.

April 4th, 2014

April 4th, 2014  Riffin

Riffin  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: