Ryan McKellar’s research sounds like it was plucked from Jurassic Park: he studies pieces of amber found buried with dinosaur skeletons. But rather than re-creating dinosaurs, McKellar uses the tiny pieces of fossilized tree resin to study the world in which the now-extinct behemoths lived.

New techniques for investigating very tiny pieces of fragile amber buried in dinosaur bonebeds could close the gaps in knowledge about the ecology of the dinosaurs, said McKellar, who is a research scientist at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Saskatchewan, Canada.

“Basically it puts a backdrop to these dinosaur digs, it tells us a bit about the habitat,” said McKellar. The amber can show what kinds of plants were abundant, and what the atmosphere was like at the time the amber was formed, he explained. Scientists can then put together details regarding what kind of habitat the dinosaur lived in and how the bonebed formed.

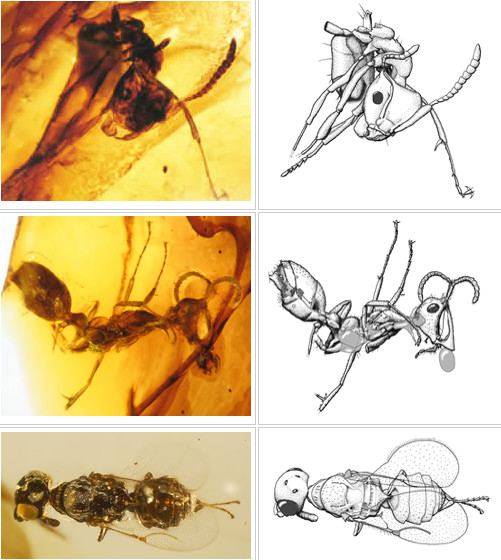

Photos and drawings of inclusions in Canadian Cretaceous amber from Grassy Lake amber, a 78-79 million year old amber in the Late Cretaceous of southern Alberta.

Credit: University of Alberta Strickland Entomology Museum specimen, R.C. McKellar; Chronomyrmex ant Grassy Lake amber, UASM specimen photo; Chronomyrmex ant Grassy Lake amber, UASM specimen drawing

The preliminary findings about dinosaur ecology, habitat, and other results from four different fossil deposits from the Late Cretaceous in Alberta and Saskatchewan, Canada, will be presented on Monday, October 20 at the Geological Society of America Annual Meeting in Vancouver, Canada.

“Just a few of these little pieces among the bones can show a lot of information,” McKellar said.

The type of amber that the scientists work with is not like the jewelry grade variety that can be made into a necklace or earrings.

“This type of amber hasn’t been pursued in the past. It is like working with a shattered candy cane,” he said. It is called friable amber, which is crumbly and fragile.

McKellar and his colleagues work with very small pieces of amber, just millimeters wide. But even samples at such a small scale can hold enormous clues to the past.

Before it hardened into amber, the sticky tree resin would often collect animal and plant material, like leaves and feathers. Scientists call these contents “inclusions,” which they study along with the surrounding amber, to look at environmental conditions, surrounding water sources, temperature, and even oxygen levels in the ancient environment.

Insects can also be included in the amber, which can be even more helpful to scientists. One example is the discovery of an aphid, stuck directly to a duck-billed dinosaur with some amber. With a find like this, scientists can track insect evolution, find their modern relatives, and see how they might have interacted with dinosaurs, said McKellar.

“When you get insects, it is like frosting on the cake — you can really round out the view of the ecosystem.”

Improvements in processing friable amber have made this research possible. Instead of the past technique of screening amber in a glycerin bath, the scientists reduce crumbling by vacuum-injecting the amber with epoxy, said McKellar.

Friable amber is widespread across the North American Continent in association with coals, and in the uncovered bonebeds, which means this area of research has expanded with the new techniques. It means scientists can sample at a finer scale, and still close some gaps in the past, especially regarding insect evolution, said McKellar.

Some of the early results of this method will be presented from amber pieces found with the skeleton of ‘Scotty’ the Tyrannosaurus rex, in Saskatchewan, Canada. McKellar will also be including case studies from three other bonebeds: the Danek Bonebed near Edmonton, Alberta; Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta; and the Pipestone Creek Pachyrhinosaurus Bonebed near Grande Prairie, Alberta.

October 22nd, 2014

October 22nd, 2014  Riffin

Riffin  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: