Nearly 30 ancient seashell species coloration patterns were revealed using ultraviolet (UV) light, according to a study published April 1, 2015 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Jonathan Hendricks from San Jose State University, CA.

Unlike their modern relatives, the 4.8-6.6 million-year-old fossil cone shells often appear white and without a pattern when viewed in regular visible light. By placing these fossils under ultraviolet (UV) light, the organic matter remaining in the shells fluoresces, revealing the original coloration patterns of the once living animals. However, it remains unclear which compounds in the shell matrix are emitting light when exposed to UV rays.

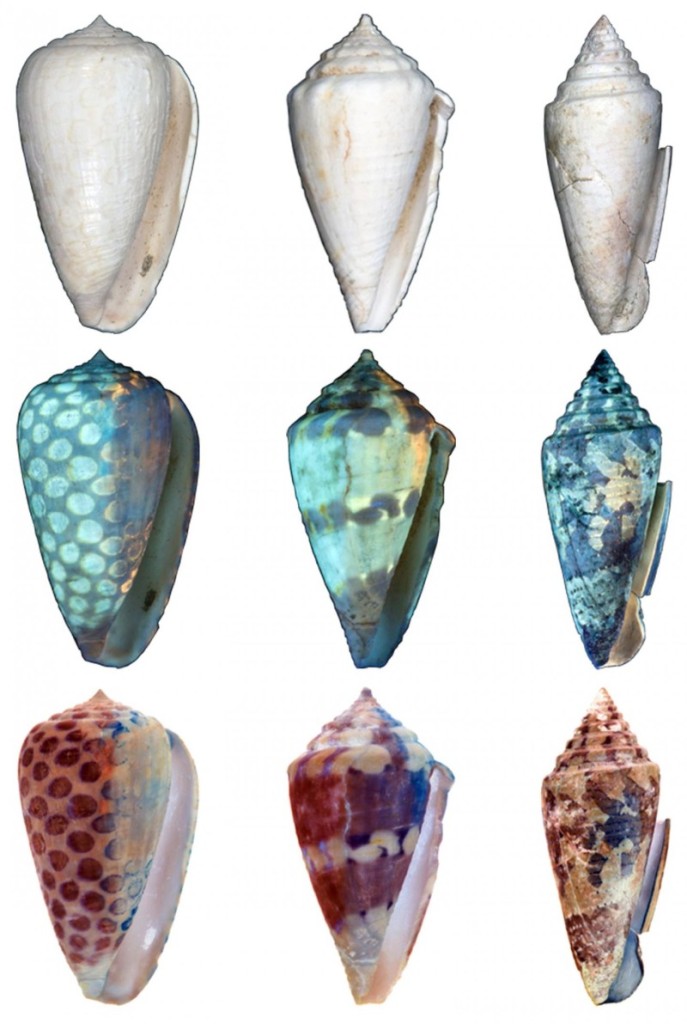

Three of the newly described species, Conus carlottae (left column), Conus garrisoni (middle column), and Conus bellacoensis (right column) photographed under regular light (top row) and ultraviolet light (middle row). The brightly fluorescing regions revealed under ultraviolet light would have been darkly pigmented in life (bottom row).

Credit: Jonathan Hendricks; CC-BY

Using this technique, the author of this study was able to view and document the coloration patterns of 28 different cone shell species from the northern Dominican Republic, 13 of which appear to be new species. Determining the coloration patterns of the ancient shells may be important for understanding their relationships to modern species.

Hendricks compared the preserved patterns with those of modern Caribbean cone snail shells and found that many of the fossils showed similar patterns, indicating that some modern species belong to lineages that survived in the Caribbean for millions of years. According to the author, a striking exception in this study was the newly described species Conus carlottae, which has a shell covered by large polka dots, a pattern that is apparently extinct among modern cone snails.

April 8th, 2015

April 8th, 2015  Riffin

Riffin  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: