Fossils are usually deformed or incompletely preserved when they are found, after sometimes millions of years of fossilization processes. Consequently, fossils have to be studied very carefully to avoid damage, and are sometimes they are difficult to access, as they might be located in remote museum collections. An international team of scientists, led by Dr. Stephan Lautenschlager from the University of Bristol now solved some of these problems by using modern computer technology, as described in a recent issue of the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

The team consisting of Dr. Stephan Lautenschlager and Professor Emily Rayfield from the University of Bristol, Professor Lindsay Zanno from the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and North Carolina State University, Dr. Perle Altangerel from the National University of Ulaanbaatar, and Professor Lawrence Witmer from Ohio University employed high-resolution X-ray computed tomography (CT scanning) and digital visualisation techniques to restore a rare dinosaur fossil.

Lead author, Dr. Stephan Lautenschlager of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences said: “With modern computer technology, such as CT scanning and digital visualisation, we now have powerful tools at our disposal, with which we can get a step closer to restore fossil animals to their life-like condition.”

The focus of the study was the skull of Erlikosaurus andrewsi, a 3-4m (10-13ft) large herbivorous dinosaur called a therizinosaur, which lived more than 90 million years ago during the Cretaceous Period in what is now Mongolia.

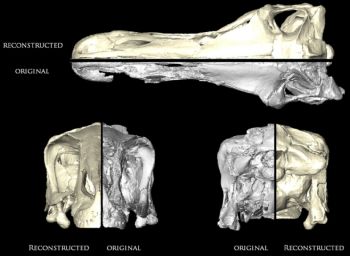

This image shows a comparison between originally preserved and digitally restored skull of the Cretaceous dinosaur Erlikosaurus andrewsi. – Image courtesy Journal of Vertebrate PaImage courtesy Journal of Vertebrate Paleontologyleontology

“The fossil skull of Erlikosaurus andrewsi is one-of-a-kind and the most complete and best preserved example known for this group of dinosaurs. As such it is of high scientific value” explains co-author Professor Emily Rayfield.

Using a digital model of the fossil, the team virtually disassembled the skull of Erlikosaurus into its individual elements. Then they digitally filled in any breaks and cracks in the bones, duplicated missing elements and removed deformation by applying retro-deformation techniques, digitally reversing the steps of deformation. In a final step, the reconstructed elements were re-assembled. This approach not only allowed the restoration of the complete skull of Erlikosaurus, but also the study of its individual elements.

However, using digital models has further advantages adds Dr. Lawrence Witmer: “Digital models allow the study of the external and internal features of a fossil. Furthermore, they can be shared quickly amongst researchers – without any risk to the actual fossil and without having to travel hundreds or even thousands of miles to see the original.”

Co-author, Dr. Lindsay Zanno agrees: “Therizinosaurs , with their pot bellies and comically enlarged claws, are arguably the most bizarre theropod dinosaurs. We know a lot about their oddball skeletons from the neck down, but this is the first time we’ve been able to digitally dissect an entire skull.”

Note: This story has been adapted from a news release issued by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology

May 20th, 2015

May 20th, 2015  Riffin

Riffin  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: