South African and Argentinian palaeontologists have discovered a new 200-million-year-old dinosaur from South Africa, and named it Sefapanosaurus, from the Sesotho word “sefapano.”

The researchers from South Africa’s University of Cape Town (UCT) and the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits University), and from the Argentinian Museo de La Plata and Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio made the announcement in the scientific journal Zoological Journal of the Linnaean Society. The paper, titled: “A new basal sauropodiform from South Africa and the phylogenetic relationships of basal sauropodomorphs,” was published online on Tuesday, 23 June 2015.

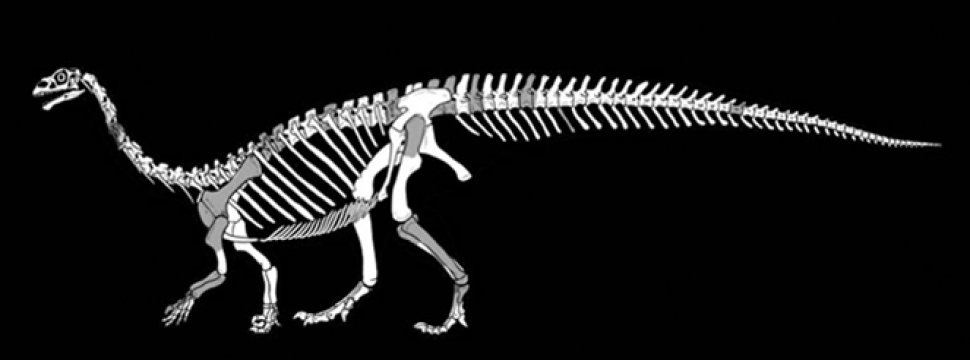

Sefapanosaurus — SA’s new Sesotho dinosaur.

Credit: Image courtesy of University of the Witwatersrand

The specimen was found in the late 1930s in the Zastron area of South Africa’s Free State province, about 30km from the Lesotho border. For many years it remained hidden among the largest fossil collection in South Africa at the Evolutionary Studies Institute (ESI) at Wits University.

A few years ago it was studied and considered to represent the remains of another South African dinosaur, Aardonyx. However, upon further study, close scrutiny of the fossilised bones has revealed that it is a completely new dinosaur.

One of the most distinctive features is that one of its ankle bones, the astragalus, is shaped like a cross. Considering the area where the fossil was discovered, the researchers aptly named the new dinosaur, Sefapanosaurus, after the Sesotho word “sefapano,” meaning “cross.”

Anusuya Chinsamy-Turan, co-author and Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at UCT, says: “The discovery of Sefapanosaurus shows that there were several of these transitional early sauropodomorph dinosaurs roaming around southern Africa about 200 million years ago.”

Dr Alejandro Otero, Argentinian palaeontologist and lead author, says Sefapanosaurus helps to fill the gap between the earliest sauropodomorphs and the gigantic sauropods. “Sefapanosaurus constitutes a member of the growing list of transitional sauropodomorph dinosaurs from Argentina and South Africa that are increasingly telling us about how they diversified.”

Says Dr Jonah Choiniere, co-author and Senior Researcher in Dinosaur Palaeobiology at the ESI at Wits University: “This new animal shines a spotlight on southern Africa and shows us just how much more we have to learn about the ecosystems of the past, even here in our own ‘backyard’. And it also gives us hope that this is the start of many such collaborative palaeo-research projects between South Africa and Argentina that could yield more such remarkable discoveries.”

Argentinian co-author, Dr Diego Pol, says Sefapanosaurus and other recent dinosaur discoveries in the two countries reveal that the diversity of herbivorous dinosaurs in Africa and South America was remarkably high back in the Jurassic, about 190 million years ago when the southern hemisphere continents were a single supercontinent known as Gondwana.

Finding a new dinosaur among old bones

Otero and Emil Krupandan, PhD-student from UCT, were visiting the ESI collections to look at early sauropodomorph dinosaurs when they noticed bones that were distinctive from the other dinosaurs they were studying.

Krupandan was working on a dinosaur from Lesotho as part of his studies when he realised the material he was looking at was different to Aardonyx. “This find indicates the importance of relooking at old material that has only been cursorily studied in the past, in order to re-evaluate past preconceptions about sauropodomorph diversity in light of new data.”

The remains of the Sefapanosaurus include limb bones, foot bones, and several vertebrae. Sefapanosaurus is represented by the remains of at least four individuals in the ESI collections at Wits University. It is considered to be a medium-sized sauropodomorph dinosaur — among the early members of the group that gave rise to the later long necked giants of the Mesozoic.

- Alejandro Otero, Emil Krupandan, Diego Pol, Anusuya Chinsamy, Jonah Choiniere. A new basal sauropodiform from South Africa and the phylogenetic relationships of basal sauropodomorphs. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2015; 174 (3): 589 DOI: 10.1111/zoj.12247

June 26th, 2015

June 26th, 2015  Riffin

Riffin  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: