A sophisticated imaging technique has allowed scientists to virtually peer inside a 10-million-year-old sea urchin, uncovering a treasure trove of hidden fossils.

The international team of researchers from the United Kingdom, Spain and Germany, including Dr Imran Rahman from the University of Bristol, studied the exceptional specimen with the aid of state-of-the-art X-ray computed tomography (CT).

Their results show that the sea urchin fossil was riddled with borings made by shelled invertebrates called bivalves. These fossilized boring bivalves were preserved inside the sea urchin in very large numbers, proving that the bivalves were using the sea urchin as an ‘island’ habitat on the seafloor, as occurs in modern oceans.

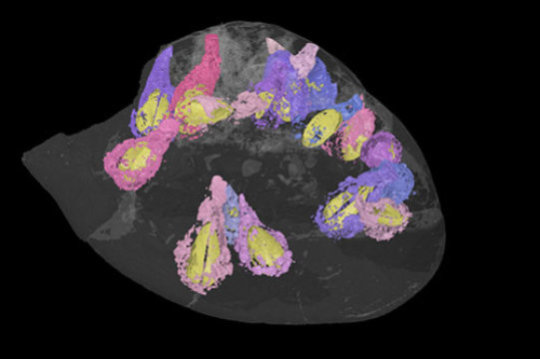

3-D reconstruction showing the fossil sea urchin and the boring bivalves inside it.

Credit: Dr Imran Rahman

The new information provided by the CT scan allowed the scientists to assign the bivalves to the genus Rocellaria, members of which are known to bore into rocks and shells today.

Lead author, Dr Rahman, a palaeontologist in Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences said: “We had no idea there would be so many bivalves inside the sea urchin. This goes to show the importance of CT scanning for understanding long-dead organisms and their ecosystems.”

Co-author Dr Zain Belaústegui, a researcher at the University of Barcelona, added: “The study confirms that the skeletons of dead animals, such as sea urchins, have been important island habitats for boring and encrusting organisms for tens of millions of years. This work also highlights how studying the traces left behind by animals, coupled with the processes that led to the formation of fossils in deep time, can provide new insights into the biology of ancient organisms and past environments.”

Co-author Professor Dr James Nebelsick from the University of Tübingen said: “This demonstrates the importance of ancient organisms not only as key members of fossil ecosystems, but also how the shells of these organisms contribute to and influence the nature of the sediments which ultimately make up the rock record.”

September 6th, 2015

September 6th, 2015  Riffin

Riffin  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: