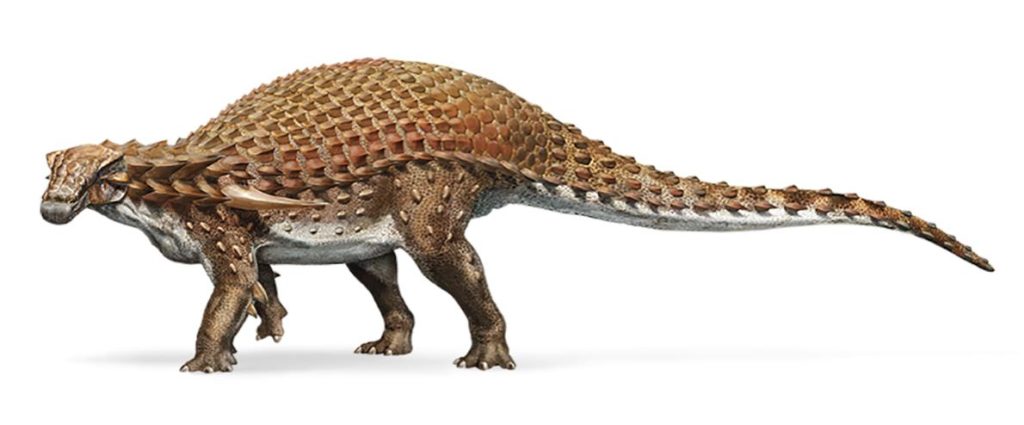

Some 110 million years ago, this armored plant-eater lumbered through what is now western Canada, until a flooded river swept it into open sea. The dinosaur’s undersea burial preserved its armor in exquisite detail. Its skull still bears tile-like plates and a gray patina of fossilized skins.

On the afternoon of March 21, 2011, a heavy-equipment operator named Shawn Funk was carving his way through the earth, unaware that he would soon meet a dragon.

That Monday had started like any other at the Millennium Mine, a vast pit some 17 miles north of Fort McMurray, Alberta, operated by energy company Suncor. Hour after hour Funk’s towering excavator gobbled its way down to sands laced with bitumen—the transmogrified remains of marine plants and creatures that lived and died more than 110 million years ago. It was the only ancient life he regularly saw. In 12 years of digging he had stumbled across fossilized wood and the occasional petrified tree stump, but never the remains of an animal—and certainly no dinosaurs.

In life this imposing herbivore—called a nodosaur—stretched 18 feet long and weighed nearly 3,000 pounds. Researchers suspect it initially fossilized whole, but when it was found in 2011, only the front half, from the snout to the hips, was intact enough to recover. The specimen is the best fossil of a nodosaur ever found.COMPOSITE OF EIGHT IMAGES PHOTOGRAPHED AT ROYAL TYRRELL MUSEUM OF PALAEONTOLOGY, DRUMHELLER, ALBERTA (ALL)

But around 1:30, Funk’s bucket clipped something much harder than the surrounding rock. Oddly colored lumps tumbled out of the till, sliding down onto the bank below. Within minutes Funk and his supervisor, Mike Gratton, began puzzling over the walnut brown rocks. Were they strips of fossilized wood, or were they ribs? And then they turned over one of the lumps and revealed a bizarre pattern: row after row of sandy brown disks, each ringed in gunmetal gray stone.

“Right away, Mike was like, ‘We gotta get this checked out,’ ” Funk said in a 2011 interview. “It was definitely nothing we had ever seen before.”

Nearly six years later, I’m visiting the fossil prep lab at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in the windswept badlands of Alberta. The cavernous warehouse swells with the hum of ventilation and the buzz of technicians scraping rock from bone with needle-tipped tools resembling miniature jackhammers. But my focus rests on a 2,500-pound mass of stone in the corner.

At first glance the reassembled gray blocks look like a nine-foot-long sculpture of a dinosaur. A bony mosaic of armor coats its neck and back, and gray circles outline individual scales. Its neck gracefully curves to the left, as if reaching toward some tasty plant. But this is no lifelike sculpture. It’s an actual dinosaur, petrified from the snout to the hips.

The more I look at it, the more mind-boggling it becomes. Fossilized remnants of skin still cover the bumpy armor plates dotting the animal’s skull. Its right forefoot lies by its side, its five digits splayed upward. I can count the scales on its sole. Caleb Brown, a postdoctoral researcher at the museum, grins at my astonishment. “We don’t just have a skeleton,” he tells me later. “We have a dinosaur as it would have been.”

For paleontologists the dinosaur’s amazing level of fossilization—caused by its rapid undersea burial—is as rare as winning the lottery. Usually just the bones and teeth are preserved, and only rarely do minerals replace soft tissues before they rot away. There’s also no guarantee that a fossil will keep its true-to-life shape. Feathered dinosaurs found in China, for example, were squished flat, and North America’s “mummified” duck-billed dinosaurs, among the most complete ever found, look withered and sun dried.

Paleobiologist Jakob Vinther, an expert on animal coloration from the U.K.’s University of Bristol, has studied some of the world’s best fossils for signs of the pigment melanin. But after four days of working on this one—delicately scraping off samples smaller than flecks of grated Parmesan—even he is astounded. The dinosaur is so well preserved that it “might have been walking around a couple of weeks ago,” Vinther says. “I’ve never seen anything like this.”

A poster for the movie Night at the Museum hangs on the wall behind Vinther. On it a dinosaur skeleton emerges from the shadows, magically brought back to life.

The remarkable fossil is a newfound species (and genus) of nodosaur, a type of ankylosaur often overshadowed by its cereal box–famous cousins in the subgroup Ankylosauridae. Unlike ankylosaurs, nodosaurs had no shin-splitting tail clubs, but they too wielded thorny armor to deter predators. As it lumbered across the landscape between 110 million and 112 million years ago, almost midway through the Cretaceous period, the 18-foot-long, nearly 3,000-pound behemoth was the rhinoceros of its day, a grumpy herbivore that largely kept to itself. And if something did come calling—perhaps the fearsome Acrocanthosaurus—the nodosaur had just the trick: two 20-inch-long spikes jutting out of its shoulders like a misplaced pair of bull’s horns.

Courtesy:Article in nat Geo

Key:WFS,World Fossil Society,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

May 13th, 2017

May 13th, 2017  Riffin

Riffin

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: