@WFS,World Fossil Society,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

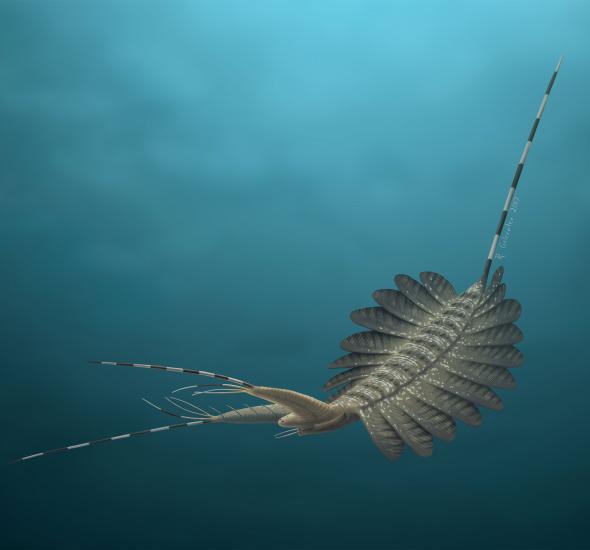

An artist’s reconstruction of the 520-million-year-old Kerygmachela kierkegaardi depicts the ancient species as a formidable ocean predator. ILLUSTRATION BY REBECCA GELERNTER, NEARBIRD STUDIOS

With help from 15 fossils recently discovered in Greenland, scientists are now able to peer inside the brain of an animal that lived 520 million years ago.

The extinct species, Kerygmachela kierkegaardi, swam in ocean waters during an evolutionary arms race called the Cambrian explosion. Flanked by 11 wrinkly flaps on each side of its body, the ancient predator sported a long tail spine and a rounded head. Its fearsome forward-facing appendages grasped prey, says UK-based paleontologist Jakob Vinther, “making lives miserable for other animals.”

Previous fossil remains of the roughly one- to ten-inch creature came from loose rocks battered by weather. But the new finds are the species’ first to escape exposure to the elements, resulting in fossil nervous tissue that is providing new evolutionary insights into the brains of panarthropods—an animal group that includes water bears (tardigrades), velvet worms, and arthropods like crustaceans and insects.

The study, led by Vinther and the Korea Polar Research Institute‘s Tae-Yoon Park, was published March 9 in the journal Nature Communications.

Contradicting some previous accounts, the team argues that this new evidence appears to show that the common ancestor of all panarthropods did not have a complex three-part brain—and neither did the common ancestor of invertebrate panarthropods and vertebrates.

Modern arthropods begin developing with a single bundle of nerve cells above their gut. They bear two other brain segments, lying beside or beneath the gut, which migrate up during development to fuse with the first nerve bundle, forming an intricate, triple-segmented brain.

That structure can be traced back through the fossil record. Kerygmachela’s relatively simple brain, preserved as thin films of carbon, includes only the foremost of the three segments present in living arthropods.

The team believes that water bears, the eight-legged micro-critters known formally as tardigrades, have a simple one-segment brain similar to what they identify in Karygmachela. Velvet worms—soft-bodied, nocturnal ambush predators—also lack a three-part brain.

So it makes sense to think that the common ancestor these animals share with arthropods also lacked a complex brain. Ditto for the organism that gave rise to both panarthropods and vertebrates, the other animal group whose brains have three segments.

Not all scientists are convinced of the details. Tardigrade brains may or may not develop based on segments at all, says Nicholas Strausfeld, a neuroscientist at the University of Arizona who was not involved in the study.

“If they’re going to say that the brain of Kerygmachela is like that of a tardigrade, you have to be really, really careful,” Strausfeld warns. “Because it might not be.” Tardigrades may lack a segmental brain altogether, instead relying on a ring of nerves around their mouths.

Vinther finds that perspective interesting. Whatever the case, he says, both ideas point to simpler ancestral nervous systems—and thus an evolutionary history in which animals’ brains evolved complex three-part structures multiple independent times.

The competition driving evolutionary arms races, Vinther says, “has led to similar outcomes that we see in different groups: eyes, complex brains, and so forth.”

Source: Article By Andrew Urevig,National Geographic

March 12th, 2018

March 12th, 2018  Riffin

Riffin

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: