@WFS,World Fossil Society,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

Descriptive anatomy of the largest known specimen of Protoichthyosaurus prostaxalis (Reptilia: Ichthyosauria) including computed tomography and digital reconstruction of a three-dimensional skull

Ichthyosaurs were a highly successful group of predatory marine reptiles that appeared in the late Early Triassic and went extinct in the early Late Cretaceous (Fischer et al., 2016). Some of the earliest forms were ‘lizard-like’ in appearance, although later forms evolved fish-shaped bodies (Motani, 2009). Species ranged in size from small-bodied forms less than one m long to giants over 20 m in length (Motani, 2005; Nicholls & Manabe, 2004; Lomax et al., 2018). Numerous Lower Jurassic ichthyosaurs have been found in the UK, the majority being from the Lyme Regis–Charmouth area in west Dorset (Milner & Walsh, 2010), the village of Street and surrounding areas in Somerset (Delair, 1969), sites around the coastal town of Whitby, Yorkshire (Benton & Taylor, 1984) and Barrow-upon-Soar, Leicestershire (Martin, Frey & Riess, 1986). Notable specimens have also been recorded from Ilminster, Somerset (Williams, Benton & Ross, 2015), Nottinghamshire (Lomax & Gibson, 2015) and Warwickshire (Smith & Radley, 2007), with various isolated occurrences at other sites across the UK (Benton & Spencer, 1995).

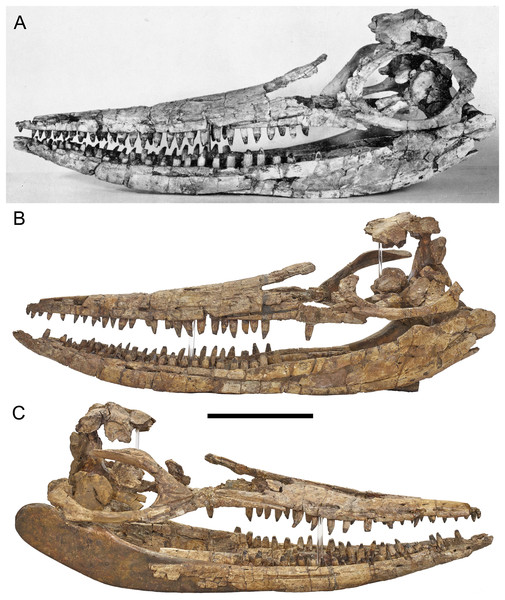

Three-dimensional skull of BMT 1955.G35.1, Protoichthyosaurus prostaxalis.

(A) Original photograph of the first skull reconstruction (left lateral view) within a couple of years of the 1955 excavation. Note that the prefrontal and postorbital are present, which we have been unable to locate in our study. (B) Skull in left lateral view, as reconstructed in 2015. (C) Skull in right lateral view, as reconstructed in 2015. Note the distinctive asymmetric maxilla with long, narrow anterior process. Teeth are not in their original positions. Scale bar represents 20 cm.

A partial ichthyosaur skeleton (BMT 1955.G35.1—Birmingham Museums Trust) was discovered in 1955 in Warwickshire, England. The specimen comprises a largely complete skull, portions of the pectoral girdle, pelvis, fore- and hindfins and numerous vertebrae and ribs. Bones of the basicranium and palate were also found, which are rarely observed in association with Lower Jurassic ichthyosaur skulls (Marek et al., 2015). The skull bones were reassembled three-dimensionally on a wood and metal frame held together with alvar, jute and kaolin dough, with missing parts carved from wood; however, some aspects were not accurately reconstructed. Museum records indicate that BMT 1955.G35.1, which has never been formally described, was originally identified as an example of Ichthyosaurus communis De la Beche & Conybeare 1821.

In 2015, as part of the development of the new Marine Worlds Gallery at the Thinktank, Birmingham Science Museum, the skull was dismantled, conserved and reassembled to be more anatomically accurate. The skull and postcranial skeleton of BMT 1955.G35.1 were publicly displayed for the first time, forming the centrepiece of this permanent gallery. The skull of BMT 1955.G35.1 is preserved in 3D and is free of matrix; this contrasts with the majority of Lower Jurassic ichthyosaur skulls, which are often flattened or displaced and preserved in matrix, enabling a more detailed description than is typical. The large size of many marine reptile skulls has precluded attempts to visualize specimens using medical imaging (but see McGowan, 1989). Given the exceptional 3D preservation, the fact it is relatively free of matrix, and access to facilities capable of imaging large specimens, we took the opportunity to scan individual cranial elements as well as the entire skull of BMT 1955.G35.1 using computed tomography (CT) before and after reassembly. CT and 3D digital reconstruction are increasingly being applied to the skulls of fossil vertebrates, including early tetrapods (Porro, Rayfield & Clack, 2015a, 2015b), dinosaurs (Rayfield et al., 2001; Lautenschlager et al., 2014, 2016; Porro, Witmer & Barrett, 2015c; Button, Barrett & Rayfield, 2016) and extinct synapsids (Wroe, 2007; Jasinoski, Rayfield & Chinsamy, 2009; Sharp, 2014; Cox, Rinderknecht & Blanco, 2015; Lautenschlager et al., 2017). The first attempt to understand the internal anatomy of the ichthyosaur skull was carried out by Sollas (1916) using serial grinding; although this method produced excellent understanding of skull anatomy, it was time-consuming, labour intensive and resulted in the destruction of the specimen. In contrast, modern medical imaging methods have been applied only to isolated regions of fossil marine reptile skulls (Kear, 2005; Fernández et al., 2011; Sato et al., 2011; Neenan & Scheyer, 2012; Herrera, Fernández & Gaspirini, 2013), with the exception of one pliosaur (Foffa et al., 2014a), one small ichthyosaur (Marek et al., 2015), for which entire skulls were CT scanned, and the skeleton of a juvenile plesiosaur (Larkin, O’Connor & Parsons, 2010).

In this paper, we use CT scanning of a large ichthyosaur skull along with careful examination of the original specimen to formally describe BMT 1955.G35.1. Based on this description we reassign the specimen to Protoichthyosaurus prostaxalis Appleby, 1979, a genus recently shown to be distinct from Ichthyosaurus based on multiple characters (Lomax, Massare & Mistry, 2017; Lomax & Massare, 2018). Furthermore, the studied specimen has an estimated maximum body length of 3.2–4 m, greater than any other known specimen of Protoichthyosaurus or Ichthyosaurus.

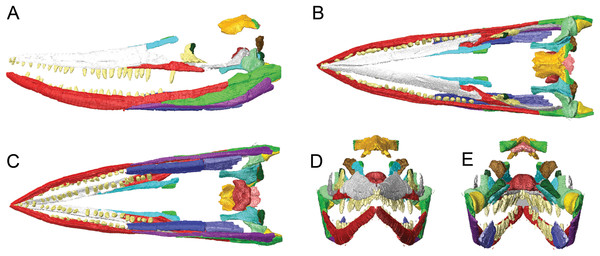

Surface models (generated from CT scan data) of the skull of BMT 1955.G35.1, Protoichthyosaurus prostaxalis.

After the removal of minor damage and duplication/mirroring of asymmetrically preserved elements, and digital articulation of individual bones to produce a more accurate digital 3D reconstruction. Displacement of the lower jaw and premaxillae and nasals are the result of deformation (see text). Left lateral (A) dorsal (B) ventral (C) anterior (D) and posterior (E) views of the upper and lower jaws. Individual bones labelled using the same colours as Figs. 2–4.

Citation: 2019. Descriptive anatomy of the largest known specimen of Protoichthyosaurus prostaxalis (Reptilia: Ichthyosauria) including computed tomography and digital reconstruction of a three-dimensional skull. PeerJ 7:e6112https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6112

@WFS,World Fossil Society,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

January 13th, 2019

January 13th, 2019  Riffin

Riffin  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: