@WFS,World Fossil Society, Athira, Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

An extremely rare collection of 160-million-year-old sea spider fossils from Southern France are closely related to living species, unlike older fossils of their kind.

These fossils are very important to understand the evolution of sea spiders. They show that the diversity of sea spiders that still exist today had already started to form by the Jurassic.

Lead author Dr Romain Sabroux from the University of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences, said: “Sea spiders (Pycnogonida), are a group of marine animals that is overall very poorly studied.

“However, they are very interesting to understand the evolution of arthropods [the group that includes insects, arachnids, crustaceans, centipedes and millipedes] as they appeared relatively early in the arthropod tree of life. That’s why we are interested in their evolution.

“Sea spider fossils are very rare, but we know a few of them from different periods. One of the most remarkable fauna, by its diversity and its abundance, is the one of La Voulte-sur-Rhône that dates back to the Jurassic, some 160 million years ago.”

Unlike older sea spider fossils, the La Voulte pycnogonids are morphologically similar (but not identical) to living species, and previous studies suggested they could be closely related to living sea spider families. But these hypotheses were restricted by the limitation of their observation means. As it was impossible to access what was hidden in the rock fossils, Dr Sabroux and his team travelled to Paris and set out to investigate this question with cutting-edge approaches.

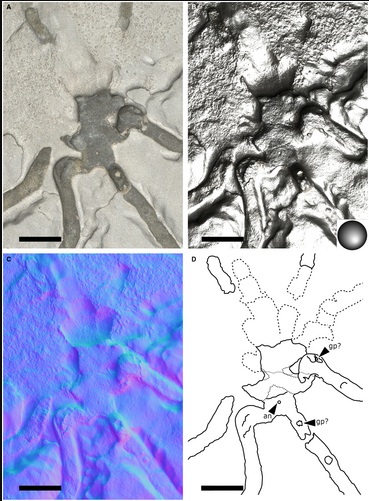

RTI of Palaeopycnogonides gracilis, MNHN.F.A88075, body region (preserved ventrally, with imprint of dorsal region anteriorly). A, default view. B, specular enhancement (circle on bottom right indicates light orientation, see Table S2 for details). C, ‘normals visualization’. D, interpretative drawing; plain black lines correspond to the outline of the fossil; dashed black lines correspond to the specimen imprints; dotted black lines correspond to the putative ovigers; grey lines correspond to the main breaks in the fossil. Abbreviations: an, anus; gp, gonopore. Scale bars represent 5 mm.

Dr Sabroux explained: “We used two methods to reinvestigate the morphology of the fossils: X-ray microtomography, to ‘look inside’ the rock, find morphological features hidden inside and reconstruct a 3D model of the fossilised specimen; and Reflectance Transformation Imaging, a picture technic that relies on varied orientation of the light around the fossil to enhance the visibility of inconspicuous features on their surface.

“From these new insights, we drew new morphological information to compare them with extant species,” explained Dr Sabroux.

This confirmed that these fossils are close relatives to surviving pycnogonids. Two of these fossils belong to two living pycnogonid families: Colossopantopodus boissinensis was a Colossendeidae while another, Palaeoendeis elmii was an Endeidae. The third species, Palaeopycnogonides gracilis, seems to belong to a family that has disappeared today.

“Today, by calculating the difference between the DNA sequences of a sample of species, and using DNA evolution models, we are able to estimate the timing of the evolution that bind these species together,” added Dr Sabroux.

“This is what we call a molecular clock analysis. But quite like a real clock, it needs to be calibrated. Basically, we need to tell the clock: ‘we know that at that time, that group was already there.’ Thanks to our work, we now know that Colossendeidae, and Endeidae were already ‘there’ by the Jurassic.”

Now, the team can use these minimal ages as calibrations for the molecular clock, and investigate the timing of Pycnogonida evolution. This can help them understand, for example, how their diversity was impacted by the different biodiversity crises that distributes over the Earth history.

They also plan to investigate other pycnogonid fossil faunae such as the fauna of Hunsrück Slate, in Germany, which dates from the Devonian, some 400 million years ago.

With the same approach, they will aim to redescribe these species and understand their affinities with extant species; and finally, to replace in the tree of life of Pycnogonida all the pycnogonid fossils from all periods.

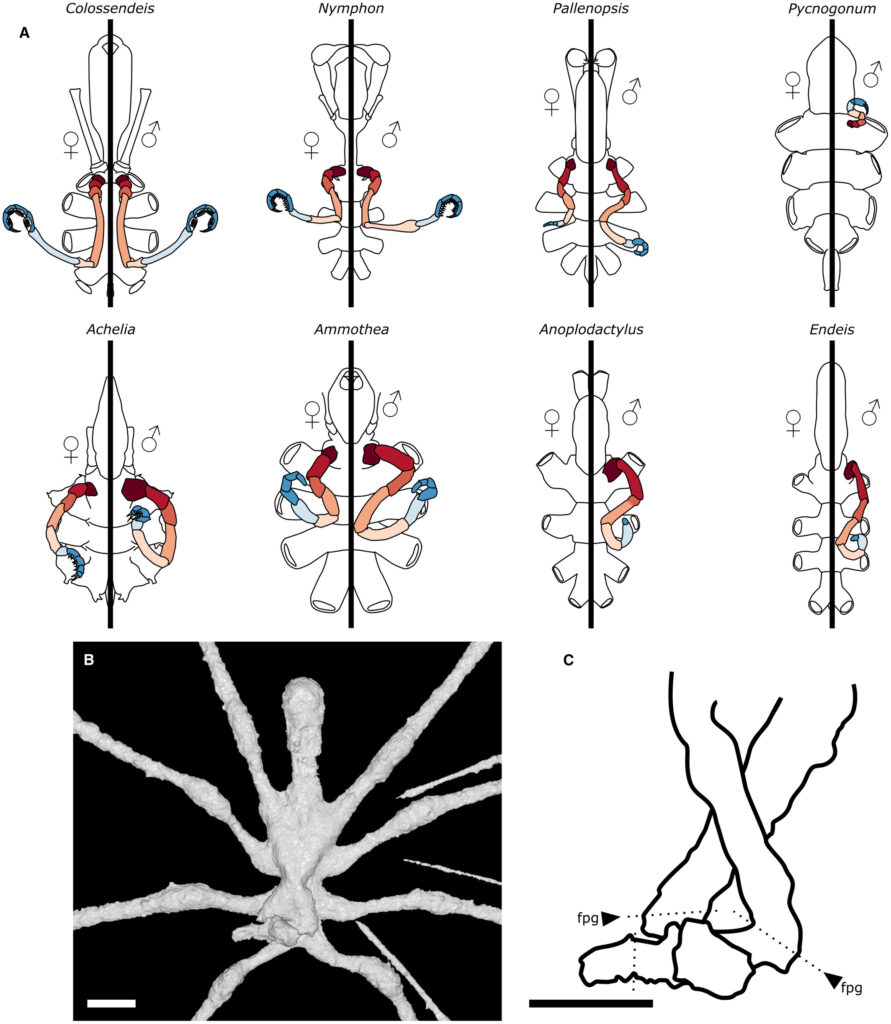

Comparison of the ovigers of Palaeoendeis elmii with some extant pantopods. A, ovigers as found in the two sexes in eight examples of modern sea spiders, using the same colour code as in Figure 1. B, close-up of the ventral view of the three-dimensional reconstruction of P. elmii, holotype MNHN.F.A49277. C, interpretative drawing of the ovigers of P. elmii; plain black lines correspond to the outline of the fossil; dotted lines correspond to the putative position of articulations. Abbreviation: fpg, femoro-patellar geniculation. Scale bars represent 2 mm.

Dr Sabroux added: “These fossils give us an insight of sea spiders living 160 million years ago.

“This is very exciting when you have been working on the living pycnogonids for years.

“It is fascinating how these pycnogonids look both very familiar, and very exotic. Familiar, because you can definitely recognize some of the families that still exist today, and exotic because of small differences like the size of the legs, the length of the body, and some other morphological characteristics that you do not find in modern species.

“Now we look forward to the next fossil discoveries — from the Jurassic and other geological periods — so that we can complete the picture!”

Journal Reference:

- Romain Sabroux, Gregory D. Edgecombe, Davide Pisani, Russell J. Garwood. New insights into the sea spider fauna (Arthropoda, Pycnogonida) of La Voulte‐sur‐Rhône, France (Jurassic, Callovian). Papers in Palaeontology, 2023; 9 (4) DOI: 10.1002/spp2.1515

August 18th, 2023

August 18th, 2023  Riffin

Riffin  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: