A fossil of Rhamphorhynchus, an early pterosaur. |

Ranging from the size of a sparrow to the size of an airplane, the pterosaurs (Greek for “wing lizards”) ruled the skies in the Jurassic and Cretaceous, and included the largest vertebrate ever known to fly: the late Cretaceous Quetzalcoatlus. The appearance of flight in pterosaurs was separate from the evolution of flight in birds and bats; pterosaurs are not closely related to either birds or bats, and thus provide a classic example of convergent evolution.

It was once thought that pterosaurs were not well adapted for active flight and relied largely on gliding and on the wind to stay in the air. However, based on analyses of pterosaur skeletal features (including work done by Berkeley’s own Kevin Padian), it is now thought that all but the largest pterosaurs could sustain powered flight. Pterosaurs had hollow bones, large brains with well-developed optic lobes, and several crests on their bones to which flight muscles attached. All of this is consistent with powered flapping flight.

|

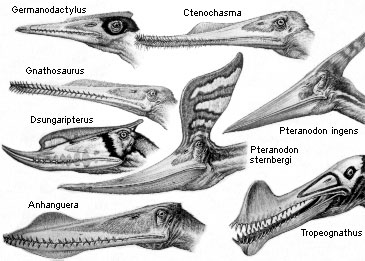

The largest pterosaur (Quetzalcoatlus, wonderfully named for the Aztec winged serpent god) had a wing span from eleven to twelve meters long (about forty feet). The wing’s main support was an amazingly elongated fourth digit in the hand. Fibers in the wing membrane added structural support and stiffness. At least some pterosaurs may have had some sort of hair-like body covering, which could very well mean that they were endothermic. Pterosaurs had a diverse range of head types, as you can tell from the pictures below. Their ability to fly probably allowed them to evolve into many niches, taking advantage of many different food sources, which would explain the range of skull morphology seen.

Pterosaurs consist of two main types (they do form a single (monophyletic) group, though): the “rhamphorhynchoids,” more properly termed the basal Pterosauria, which had long tails, and their descendants the “pterodactyloids,” which had shorter tails. Why is the term “rhamphorhynchoid” an invalid one? Since the later Pterosauria (the”pterodactyloids”) are the descendants of the basal Pterosauria, “rhamphorhynchoid” is a paraphyletic term, which phylogenetic researchers shy away from using. The basal Pterosauria (including Rhamphorhynchus, pictured at the top of this page) first appeared in the Late Triassic and all went extinct at the end of the Jurassic. The more derived pterosaurs (including Pteranodon, below) that were the descendants of this group appear first in Late Jurassic rocks, and the last of them died out at the end of the Cretaceous. Below is a mounted skeleton of Pteranodon ingens on display at the UCMP. Click on the picture to view an enlargement.

What was Pteranodon like?

Pteranodon. Photo by Dave Smith, © 2005 UCMP. |

The genus Pteranodon includes several species of large pterosaurs from the Cretaceous period in North America. As you can tell from this photo, it had a large crested head, a huge wingspan (some 20-25 feet; the UCMP specimen is about 22 feet), and a comparatively small body. This is deceiving; it looks like the head and wing bones were too bulky, and the hindlimbs appear small and weak. Not so; the bones of Pteranodon are actually completely hollow (about 1 millimeter thick!), and were quite light. The whole animal probably weighed about 25 pounds, only slightly heavier than the largest flying birds. The hindlimbs are actually perfectly sized for the body; Pteranodon would have been capable of bipedal terrestrial movement (but was no rapid runner, unlike its ancestors, some of whom seem to have been fast bipedal runners). The wing bones look thick because a large bone diameter is more vital for resisting the bending stresses involved in flight (as opposed to large bone thickness, which is important for resisting compressive forces, such as those imposed by the weight of a large body), so actually the wings of Pteranodon were more than adequate for flight.

Pteranodon was almost certainly a soaring animal; it used rising warm air to maintain altitude; a common strategy among large winged animals (among birds, albatrosses and vultures are adept at soaring). Its scooplike beak was used for snapping up fish as it soared over the oceans that it nested by. A good modern analog for Pteranodon would be the pelican.

Source: University of California Museum of Paleontology informations.

June 12th, 2013

June 12th, 2013  Riffin

Riffin  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: