Break-up of the supercontinent Gondwana about 130 Million years ago could have lead to a completely different shape of the African and South American continent with an ocean south of today’s Sahara desert, as geoscientists from the University of Sydney and the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences have shown through the use of sophisticated plate tectonic and three-dimensional numerical modelling.

The study highlights the importance of rift orientation relative to extension direction as key factor deciding whether an ocean basin opens or an aborted rift basin forms in the continental interior.

For hundreds of millions of years, the southern continents of South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia, and India were united in the supercontinent Gondwana. While the causes for Gondwana’s fragmentation are still debated, it is clear that the supercontinent first split along along the East African coast in a western and eastern part before separation of South America from Africa took place. Today’s continental margins along the South Atlantic ocean and the subsurface graben structure of the West African Rift system in the African continent, extending from Nigeria northwards to Libya, provide key insights on the processes that shaped present-day Africa and South America.

Christian Heine (University of Sydney) and Sascha Brune (GFZ) investigated why the South Atlantic part of this giant rift system evolved into an ocean basin, whereas its northern part along the West African Rift became stuck.

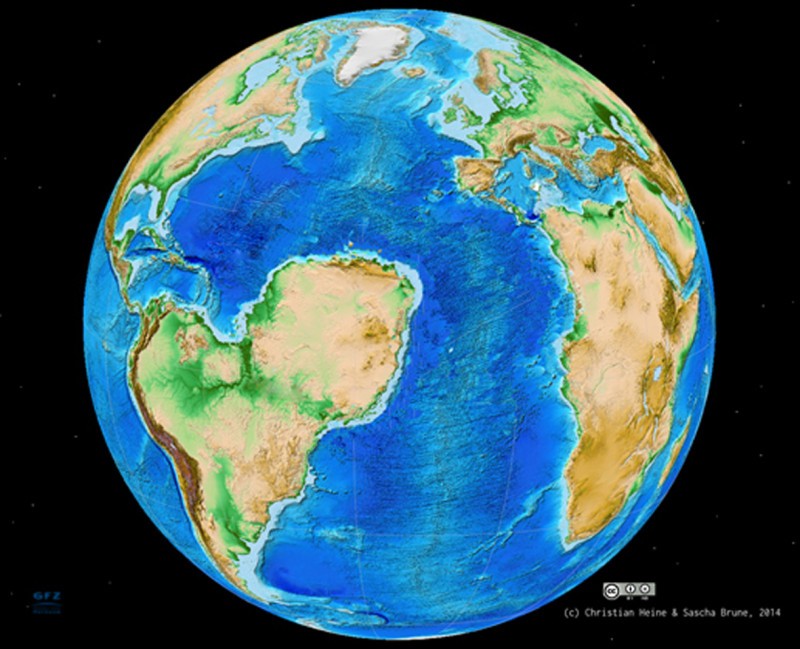

A hypothetical model of the circum-Atlantic region at present-day, if Africa had split into two parts along the West African Rift system. Here, the north-west part of present day Africa would have moved with the South American continent, forming a “Saharan Atlantic ocean”.

Credit: Sascha Brune/Christian Heine

“Extension along the so-called South Atlantic and West African rift systems was about to split the African-South American part of Gondwana North-South into nearly equal halves, generating a South Atlantic and a Saharan Atlantic Ocean,” geoscientist Sascha Brune explains. “In a dramatic plate tectonic twist, however, a competing rift along the present-day Equatorial Atlantic margins, won over the West African rift, causing it to become extinct, avoiding the break-up of the African continent and the formation of a Saharan Atlantic ocean.”

The complex numerical models provide a strikingly simple explanation: the larger the angle between rift trend and extensional direction, the more force is required to maintain a rift system. The West African rift featured a nearly orthogonal orientation with respect to westward extension which required distinctly more force than its ultimately successful Equatorial Atlantic opponent.

Source: Helmholtz Centre Potsdam – GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences. “How Earth might have looked: How a failed Saharan Atlantic Ocean rift zone sculped Africa’s margin.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 28 February 2014. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/02/140228210545.htm>.

March 4th, 2014

March 4th, 2014  Riffin

Riffin  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: