@WFS,World Fossil Society,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

The amber containing the dinosaur-era bird had been polished partway through the body, allowing researchers to peer inside the skull and chest cavity and chemically map its exposed soft tissues.Photograph by R.C. McKellar, Royal Saskatchewan Museum

The squashed remains of a small bird that lived 99 million years ago have been found encased in a cloudy slab of amber from Myanmar (Burma). While previous birds found in Burmese amber have been more visually spectacular, none of them have contained as much of the skeleton as this juvenile, which features the back of the skull, most of the spine, the hips, and parts of one wing and leg. (Help us celebrate 2018 as the Year of the Bird.)

The newfound bird is also special because researchers can more clearly see the insides of the young prehistoric creature, says study co-author Ryan McKellar of the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Regina, Canada.

“The amber is turbid, with lots of little wood particulates. It looks like it was produced on or near the forest floor,” McKellar says. This means the external view of the bird isn’t great, but the interior is much more exciting.

“When it was being prepared in Myanmar, they polished through the front half of the specimen, which gave us an exposed view into the chest cavity and the skull,” McKellar says.

The discovery adds to a remarkable collection of Cretaceous-period fossils from the amber deposits in northern Myanmar’s Hukawng Valley. In the past few years, the region has also yielded several beautiful bird wings, the spectacular feathered tail of a small carnivorous dinosaur, and the outline of an entire hatchling bird. In December, researchers even revealed ticks in amber that may have feasted on dinosaurs.

“This Myanmar fossil deposit is clearly game-changing. It’s arguably the more important breakthrough for understanding bird evolution right now,” says Julia Clarke, an expert on the evolution of birds and flight at the University of Texas at Austin.

“We used to think we’d never have a whole bird in Cretaceous amber, but now we have multiple examples.”

Foamy and Squashed

Lida Xing, lead author of the paper detailing the specimen in the journal Science Bulletin, says that when he first saw the newfound bird being sold for jewelry in Myanmar in 2015, his heart began to beat very fast.

The team was lucky to acquire the bird for the Dexu Institute of Paleontology in Chaozhou, China. Birds in amber can sometimes sell for up to $500,000, putting them beyond the reach of scientists, says Xing, a paleontologist at the China University of Geosciences in Beijing.

He estimates that this is only the second bird in Burmese amber that’s been described by scientists and published in a journal. But he thinks as many as six have been discovered so far, around half of which have disappeared into the hands of private collectors.

Based on their analysis, supported in part by National Geographic, the team says that the young bird fell into the Cretaceous tree resin either dead or alive, and moisture caused the resin to foam slightly, later creating the cloudy amber. Some of the bones and soft tissues were weathered away, and sediment got trapped inside the spaces.

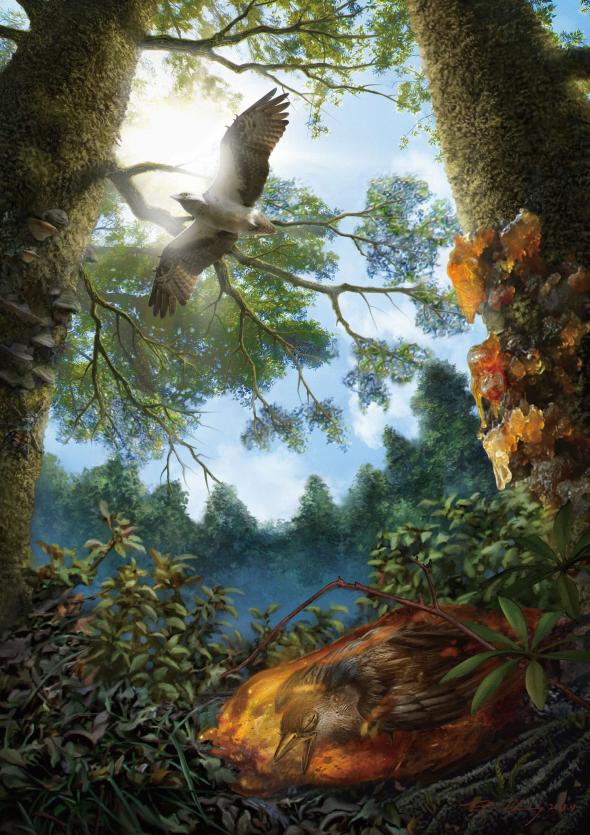

An illustration shows the young Cretaceous bird trapped in tree resin, which would eventually fossilize into amber.Illustration by Cheung Chung Tat

“A subsequent resin flow sealed the remains to protect them from further weathering or dissolution, but the amber was later squished, shattering many of the bones,” says McKellar. “All of this is now trapped in a wafer of amber about as large as a belt buckle.”

The bird itself is around 2.4 inches long and is perhaps slightly older than the 1.8-inch hatchling bird described last year. The structure of its feathers and skeleton suggests it was an enantiornithine, a type of primitive bird that went extinct with the non-avian dinosaurs 66 million years ago. (Here’s what happened on the day the dinosaurs died.)

“Even though they are hatchlings, they already have a full set of flight feathers,” McKellar says. “They have a weakly developed rachis, or central shaft, so they may not have been excellent flyers.”

In life, the bird would have had teeth in its beak and would have been dark chestnut or walnut in color, with fuzzy feathers on its head and neck.

Nest Mates

“It’s always exciting when a vertebrate fossil is found in amber, especially Cretaceous amber,” says George Poinar, a paleobiologist at Oregon State University in Corvallis, whose research on fossilized insects in amber inspired the plot of Jurassic Park.

Assigning it to the enantiornithine birds makes sense, he adds, as they were common at that time. But it’s a pity “that the two diagnostic features of that family are missing: the toothed beak and clawed fingers on the wings.”

Poinar speculates that the fledgling may have been attacked by a predator and knocked out of the nest into resin oozing from the same tree, and that some of the plant fragments and a cockroach also found trapped in the amber piece may have originated in the nest.

“Cockroaches are general scavengers, and finding them in nesting material would not be a surprise,” he says.

With time and luck, McKellar says, the team hopes to have a whole growth series of enantiornithine birds in Burmese amber. There’s certainly no shortage of raw material to comb through—in 2015 alone, an estimated 10 tons of amber were extracted from the Hukawng Valley.

Source: Article By ,news.nationalgeographic.com

@WFS,World Fossil Society,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

February 4th, 2018

February 4th, 2018  Riffin

Riffin  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: