@WFS,World Fossil Society,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

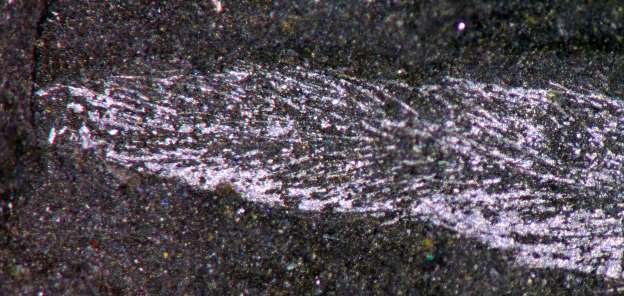

The defining specimen of Koreamegops samsiki, a newfound species of spider that lived in what is now South Korea between 106 and 112 million years ago.PHOTOGRAPH BY PAUL ANTONY SELDEN

IF YOU COULD time-travel to Korea 110 million years ago, you’d see an eerie spectacle if you walked out at night with a flashlight: Each sweep of your beam would make the landscape sparkle as innumerable spider eyes glinted in the dark.

In a new study in the Journal of Systematic Paleontology, a team led by Korea Polar Research Institute paleontologist Tae-Yoon Park unveils ten fossils of tiny spiders, each less than an inch wide. The remains contain two new species and a first for paleontology: a spider’s version of night-vision goggles.

In some animals’ eyeballs, a membrane called the tapetum (tuh-PEE-tuhm) sits behind the retina and reflects light back through it. If you’ve ever seen a cat’s eyes seem to glow green at night, that’s their tapeta at work. By giving the retinas a second chance to absorb light, tapeta boost the night vision of moths, cats, owls, and many other nocturnal animals. So, too, in these ancient spiders, whose silvery tapeta still shine in the fossils.

“They’re so reflective—they clearly stick out at you,” says study coauthor Paul Selden, a paleontologist at the University of Kansas. “That was a sort of eureka moment.”

The find sheds further light on the ancient behavior of spiders, some of modern Earth’s most important predators by mass.

The eyes have it

Some of the newfound spiders belong to an extinct group known as the lagonomegopids, some of which loosely resembled today’s jumping spiders. The new fossils are the first lagonomegopids ever found in rock—all previous fossils of the group come from amber, or fossilized tree resin. (See a feathered dinosaur’s tail preserved in amber.)

Before this study, all known fossils of lagonomegopids—an extinct group of spiders—had been found in amber, including this 99-million-year-old specimen. J. dalingwateri and K. samsiki are the first lagonomegopids ever found fossilized in rock.PHOTOGRAPH BY PAUL ANTONY SELDEN

The landscape these spiders knew was very different from Korea today. Some 110 million years ago, the southern Korean peninsula was a shallow basin that formed as a nearby volcanic ridge expanded. Fish and bivalves thrived in the basin’s lakes and rivers. Dinosaurs and pterosaurs lived nearby, judging by the teeth they left behind.

After getting washed out into a lake within this basin, the spiders’ bodies ended up buried in the lake’s sediments. Minerals then replaced the spiders’ flesh: Even today, their legs show traces of the hairs that once covered them. The spiders laid undisturbed until several years ago, when collectors found them in two construction sites near the city of Jinju, one of which is now a parking lot.

Park’s team later learned that the fossils were of many different spider types, including the two new lagonomegopid species. One of the newly described spiders, Koreamegops samsiki, is named for Samsik Lee, the Korean collector who found it. The other, Jinjumegops dalingwateri, is named for British arachnologist John Dalingwater, a mentor of Selden’s who died of Parkinson’s disease in 2018.

Both new species have tapeta and enlarged secondary eyes, much like today’s wolf spiders and the prey-snaring spider Deinopis spinosa. While the fossil spiders’ eyes would have glittered as wolf spiders’ eyes do today, it’s far from a given that they hunted their prey in a similar way.

“The eyes [of K. samsiki and J. dalingwateri] are more at the corners of their head rather than the front, which is a bit of a mystery,” Selden says.

Depending on how the spiders’ retinas were built, their tapeta may have made their vision blurrier, Morehouse adds. Today’s nocturnal spiders get around this issue by spacing out the light-sensitive parts of their retinas. It’s unknown whether the ancient spiders struck a similar balance—but finding more fossils would help.

“How these fossil spiders navigated such tradeoffs will probably remain unknown unless an even better set of fossils shows up,” Morehouse writes. “I’d be excited to see what future studies uncover.”

Source: Article by Michael Greshko ,National Geographic’s science desk.

@WFS,World Fossil Society,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

January 31st, 2019

January 31st, 2019  Riffin

Riffin

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: