Giant insects ruled the prehistoric skies during periods when Earth’s atmosphere was rich in oxygen. Then came the birds. After the evolution of birds about 150 million years ago, insects got smaller despite rising oxygen levels, according to a new study by scientists at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

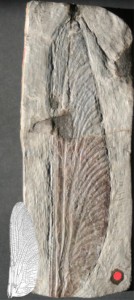

Insects reached their biggest sizes about 300 million years ago during the late Carboniferous and early Permian periods. This was the reign of the predatory griffinflies, giant dragonfly-like insects with wingspans of up to 28 inches (70 centimeters). The leading theory attributes their large size to high oxygen concentrations in the atmosphere (over 30 percent, compared to 21 percent today), which allowed giant insects to get enough oxygen through the tiny breathing tubes that insects use instead of lungs.

The new study takes a close look at the relationship between insect size and prehistoric oxygen levels. Matthew Clapham, an assistant professor of Earth and planetary sciences at UC Santa Cruz, and Jered Karr, a UCSC graduate student who began working on the project as an undergraduate, compiled a huge dataset of wing lengths from published records of fossil insects, then analyzed insect size in relation to oxygen levels over hundreds of millions of years of insect evolution. Their findings are published in the June 4 online early edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

“Maximum insect size does track oxygen surprisingly well as it goes up and down for about 200 million years,” Clapham said. “Then right around the end of the Jurassic and beginning of the Cretaceous period, about 150 million years ago, all of a sudden oxygen goes up but insect size goes down. And this coincides really strikingly with the evolution of birds.”

With predatory birds on the wing, the need for maneuverability became a driving force in the evolution of flying insects, favoring smaller body size.

The findings are based on a fairly straightforward analysis, Clapham said, but getting the data was a laborious task. Karr compiled the dataset of more than 10,500 fossil insect wing lengths from an extensive review of publications on fossil insects. For atmospheric oxygen concentrations over time, the researchers relied on the widely used “Geocarbsulf” model developed by Yale geologist Robert Berner. They also repeated the analysis using a different model and got similar results.

The study provided weak support for an effect on insect size from pterosaurs, the flying reptiles that evolved in the late Triassic about 230 million years ago. There were larger insects in the Triassic than in the Jurassic, after pterosaurs appeared. But a 20-million-year gap in the insect fossil record makes it hard to tell when insect size changed, and a drop in oxygen levels around the same time further complicates the analysis.

Another transition in insect size occurred more recently at the end of the Cretaceous period, between 90 and 65 million years ago. Again, a shortage of fossils makes it hard to track the decrease in insect sizes during this period, and several factors could be responsible. These include the continued specialization of birds, the evolution of bats, and a mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous.

“I suspect it’s from the continuing specialization of birds,” Clapham said. “The early birds were not very good at flying. But by the end of the Cretaceous, birds did look quite a lot like modern birds.”

Clapham emphasized that the study focused on changes in the maximum size of insects over time. Average insect size would be much more difficult to determine due to biases in the fossil record, since larger insects are more likely to be preserved and discovered.

“There have always been small insects,” he said. “Even in the Permian when you had these giant insects, there were lots with wings a couple of millimeters long. It’s always a combination of ecological and environmental factors that determines body size, and there are plenty of ecological reasons why insects are small.”

June 5th, 2012

June 5th, 2012  riffin

riffin

Posted in

Posted in