@WFS,World Fossil Society,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

Citation: “Late Permian (Lopingian) terrestrial ecosystems: A global comparison with new data from the low-latitude Bletterbach Biota” .MassimoBernardiabFabio MassimoPettiacEvelynKustatscherdeMatthiasFranzfChristophHartkopf-FrödergConrad C.LabandeirahijTorstenWapplerkJohanna H.A.van Konijnenburg-van CittertlBrandon R.PeecookmKenneth D.Angielczykm

The late Palaeozoic is a pivotal period for the evolution of terrestrial ecosystems. Generalised warming and aridification trends resulted in profound floral and faunal turnover as well as increased levels of endemism. The patchiness of well-preserved, late Permian terrestrial ecosystems, however, complicates attempts to reconstruct a coherent, global scenario. In this paper, we provide a new reconstruction of the Bletterbach Biota (Southern Alps, NE Italy), which constitutes a unique, low-latitude record of Lopingian life on land. We also integrate floral, faunal (from skeletal and footprint studies), and plant–insect interaction data, as well as global climatic interpretations, to compare the composition of the 14 best-known late Permian ecosystems. The results of this ecosystem-scale analysis provide evidence for a strong correlation between the distribution of the principal clades of tetrapod herbivores (dicynodonts, pareiasaurs, captorhinids), phytoprovinces and climatic latitudinal zonation. We show that terrestrial ecosystems were structured and provincialised at high taxonomic levels by climate regions, and that latitudinal distribution is a key predictor of ecosystem compositional affinity. A latitudinal diversity gradient characterised by decreasing richness towards higher latitudes is apparent: mid- to low-latitude ecosystems had the greatest amount of high-level taxonomic diversity, whereas those from high latitudes were dominated by small numbers of higher taxa. The high diversities of tropical ecosystems stem from their inclusion of a mixture of late-occurring holdovers from the early Permian, early members of clades that come to prominence in the Triassic, and contemporary taxa that are also represented in higher latitude assemblages. A variety of evidence suggests that the Permian tropics acted as both a cradle (an area with high origination rates) and museum (an area with low extinction rates) for biodiversity.

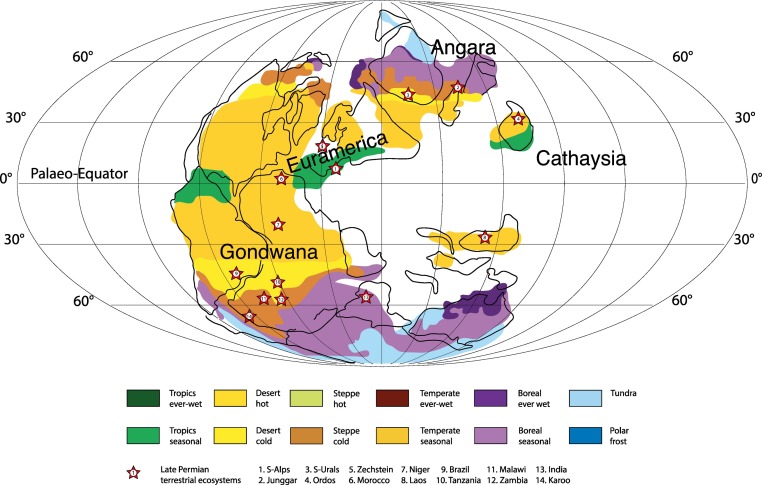

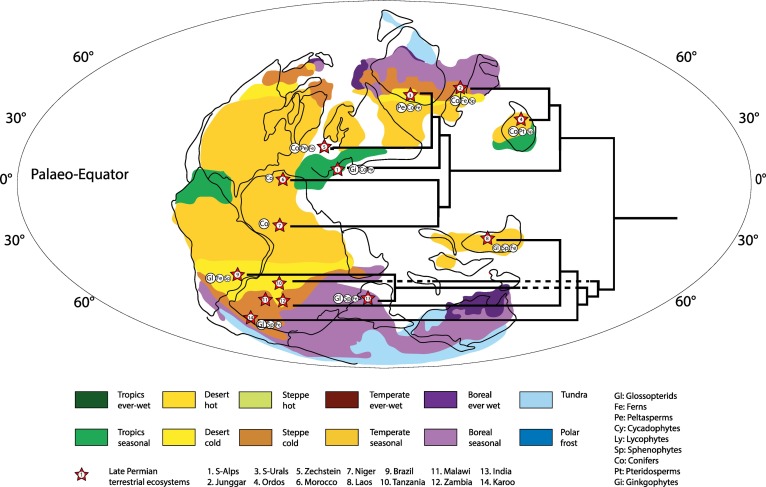

Lopingian climatic zones (colours) and phytoprovinces (bold text) (modified after Roscher et al., 2008, 2011). Stars mark the 14 best-documented late Permian terrestrial ecosystems discussed in the text.

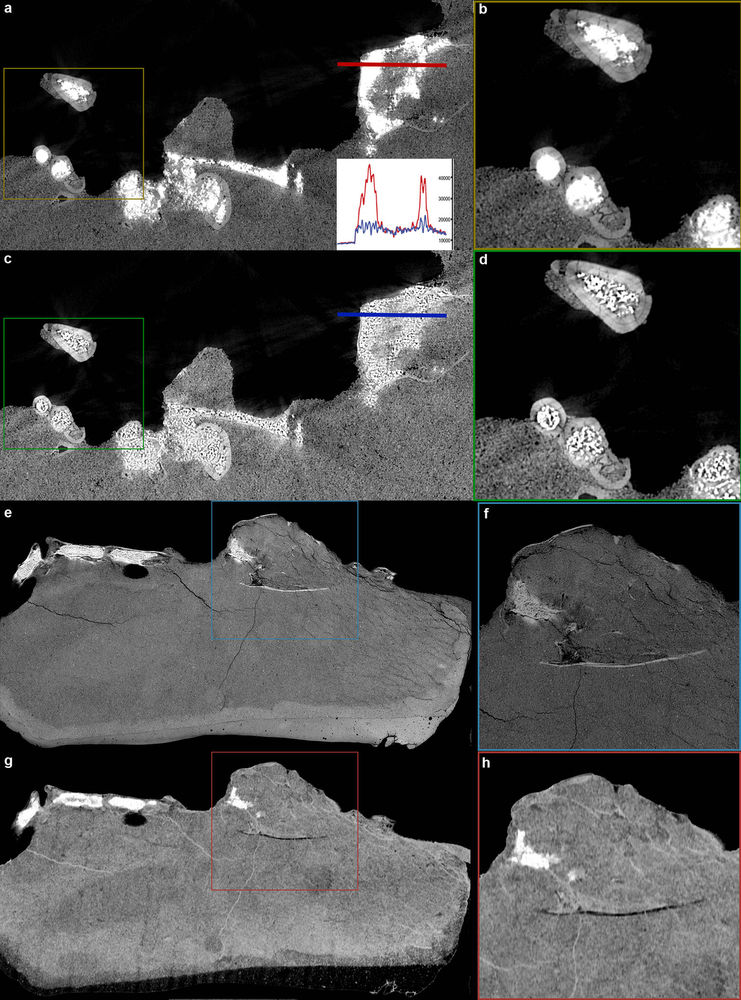

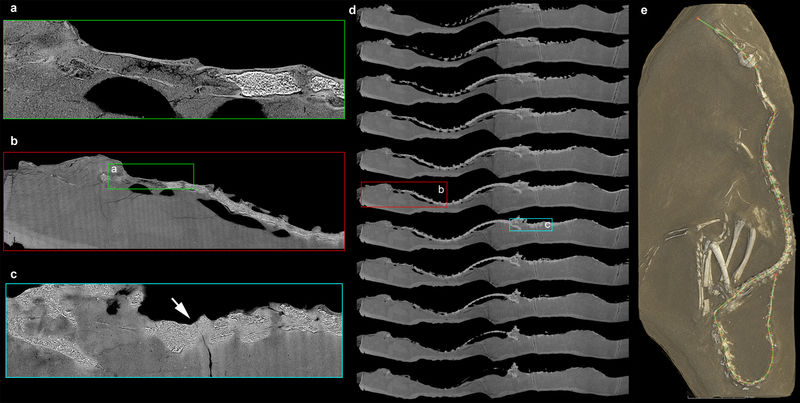

Insect-mediated damage at the Bletterbach Gorge. A–D. Insect interactions on conifers. A. Excision of leaf apex (DT13) on Ortiseia leonardii (PAL 2020); scale bar = 1 mm. B. Circular to ellipsoidal galls on the primary vein (DT33) on Pseudovoltzia sp. (PAL859); scale bar = 1 mm. C. Cluster of elliptical piercing-and-sucking scars (DT48; black arrows) on Quadrocladus sp. (PAL 1448); scale bar = 1 mm. D. Woody spheroidal leaf gall on Quadrocladus sp. (PAL 1464); scale bar = 1 mm. E. Insect interactions cycadophytes with extensive oviposition on the midvein (DT76; white arrows) and on the lamina (DT101; black arrows) on Taeniopteris sp. (PAL 1532); scale bar = 10 mm. F–J. Insect interactions ginkgophytes. F. Margin feeding (DT12; black arrows) at the margin of an unaffiliated ginkgophyte (PAL 821); scale bar = 5 mm. G. Window feeding (DT130) with a distinct callus on an unaffiliated ginkgophyte (PAL 1455); scale bar = 2 mm. H. Margin feeding (DT12) at the margin of an unaffiliated ginkgophyte (PAL 1445); scale bar = 10 mm; enlarged in I. and J., scale bars = 5 mm. K. Margin feeding (DT12) of a Dicranophyllum-like leaf (PAL 997); scale bar = 3 mm. L. Wood boring (DT160) on an unidentified axis (PAL 2016); scale bar = 1 mm. M. Seed predation (DT74) on PAL 1088; scale bar = 1 mm.

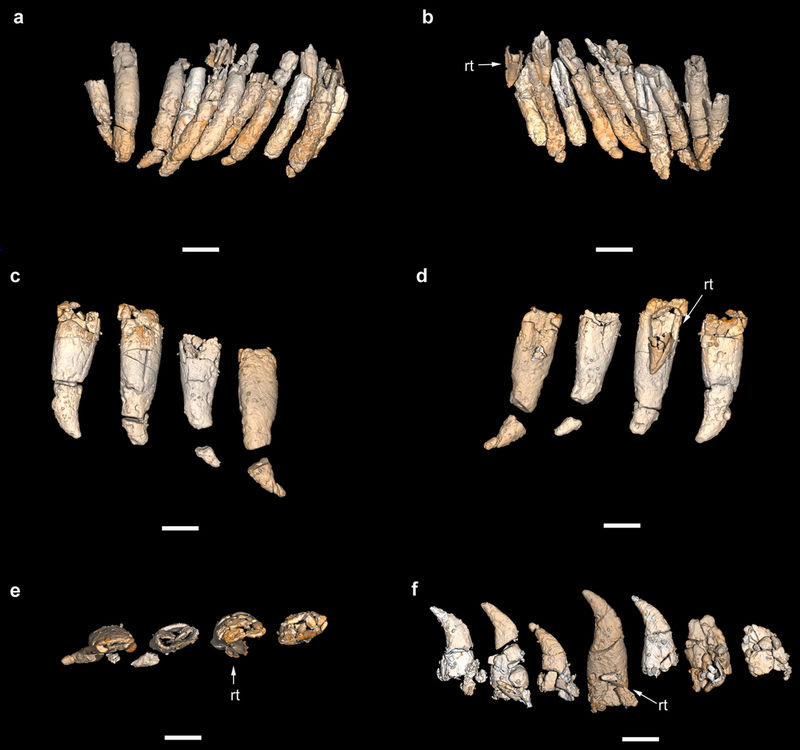

Simplified trophic network architecture of the Bletterbach biota (Southern Alps), showing the inferred complex interactions of floral and faunal communities; 1) faunivorous therapsids; 2) archosauromorphs; 3) pareiasaurs; 4) herbivorous therapsids; 5) possible captorhinids; 6) indet. therapsids; 7) basal neodiapsids; 8) insects; 9) sphenophytes; 10) seed ferns; 11) ginkgophytes; 12) conifers; 13) taeniopterids.

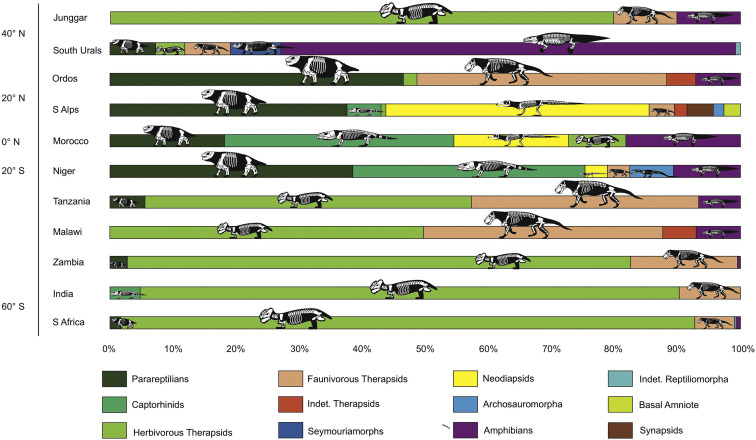

Faunal composition and relative abundances in the 14 best-documented late Permian terrestrial ecosystems, plotted against palaeolatitudes. Lopingian latitudinal gradient shows poleward decline in tetrapod richness at high taxonomic levels.

Whole ecosystem affinities based on relative abundance of the main faunal and floral groups. Climate, latitude and tectonic history control the affinity of the 14 best-documented Lopingian ecosystems. Note in particular the Eurasian affinity of north Gondwana ecosystems and the southern affinity of south Cathaysian (Laos) ecosystems.

Citation: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.10.002

@WFS,World Fossil Society,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

December 16th, 2017

December 16th, 2017  Riffin

Riffin