A mysterious group of balanced rocks that ought to have been knocked flat centuries ago may have let slip a deep, dark secret about the San Andreas Fault, according to a new study.

For two decades a handful of researchers have been uncovering the power of centuries-old earthquakes by studying how easily it would be to tip the balanced rocks that dot the countryside: If precariously balanced rocks have stood for centuries, then the risk or frequency of large quakes is probably low in that area. But if only very sturdy balanced rocks can be found, then it could be that more frequent strong quakes knocked down everything else.

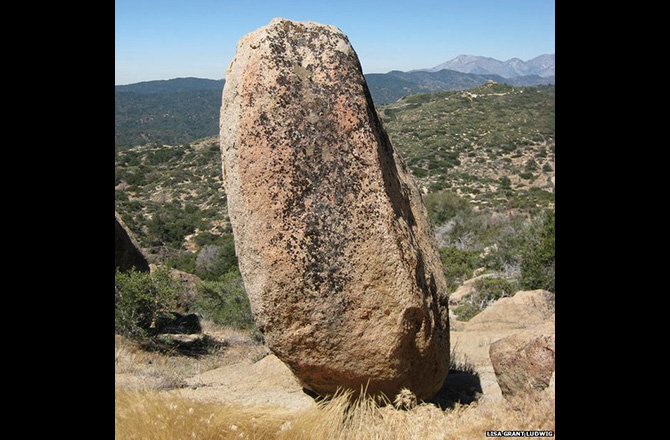

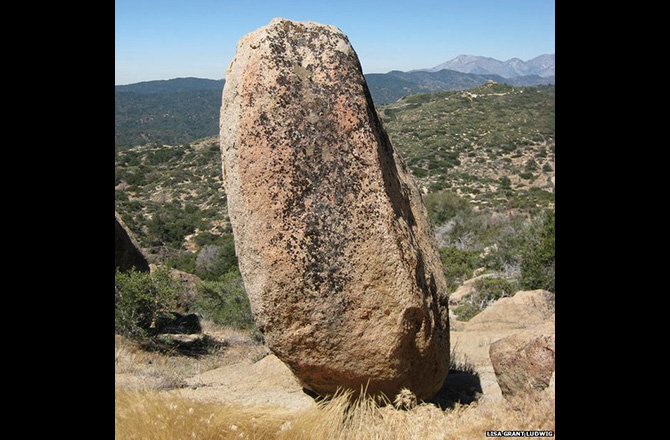

A group of delicately balanced rocks have been standing for thousands of years close to the active San Andreas and San Jacinto faults. Lisa Grant Ludwig

“So it’s indirect evidence of what has not happened,” explained Lisa Grant Ludwig, the lead author of a paper about the balanced rocks in the latest issue of the journal Seismological Research Letters. And that’s important for drawing up good earthquake hazard maps and establishing adequate building codes.

Then a few years ago researchers found a group of balanced rocks that seem to defy common sense, located in the San Bernadino Mountains, northeast of Los Angeles. These rocks are far too close to the large San Jacinto Fault, right where it edges near the even more notorious San Andreas Fault.

“Based on what we know about the physics of earthquakes and fault ruptures, these shouldn’t be here,” said Ludwig. So Ludwig and her colleagues looked for the possible reasons the rocks have remained. “We kind of had a process of elimination.”

One possibility is that the balanced rocks are much younger than they appear and so they have not been around long enough to experience a less frequent, but strong earthquake. Maybe they are even younger than the great earthquakes of 1812 and 1857, the former of which famously toppled the big church, which still lies in ruins, at San Juan Capistrano.

To find out, the rocks were dated using cosmogenic dating techniques. These allow researchers to determine how long a rock surface has been exposed to the sky. That showed the rocks were in place for up to 18,000 years — plenty of time to have experienced lots of San Andreas and San Jacinto quakes.

To find out, the rocks were dated using cosmogenic dating techniques. These allow researchers to determine how long a rock surface has been exposed to the sky. That showed the rocks were in place for up to 18,000 years — plenty of time to have experienced lots of San Andreas and San Jacinto quakes.

Another possibility is that the rocks really aren’t as fragile as they look. There are a few ways to estimate the fragility of the rocks, including directly pushing to see if they move and modeling the rocks and working out their center of gravity, to see how they might respond to shaking. But that was a dead end as well.

“They look fragile and the data came back that they’re fragile too,” Ludwig said. “Finally it occurred to us that the San Andreas and San Jacinto faults are very close together — just 2 to 2 1/2 kilometers apart there. We began to wonder if it was a step over.”

A step over is when one fault ruptures and then the rupture ends and jumps over to a nearby fault, no more than about 2 1/2 miles (4 kilometers) away. These have been known to happen, and usually suggest that the two faults are really connected deep underground.

Modeling of the faults by Ph.D. student Julian Lozos, a coauthor on the paper, showed that just such a thing could happen between the San Jacinto and the San Andreas, and that it could create a region of less shaking where the balanced rocks are found.

“The modeling shows that … near the nucleation point (of a quake in that area) you can have rather low shaking,” said seismic hazard scientist Mark Stirling at GNS Science in New Zealand. “She might actually be identifying an area of relatively low shaking.”

“It’s potentially quite important,” Stirling said, and underscores how simplistic ground movement models are and how localized shaking can actually be quite variable.

“We can’t know for sure,” said Ludwig of their conclusions, but as more and more pieces of the puzzle come together, step over of ruptures and a deeper connection between the two big faults is looking more and more like the answer.

Ref: Article by by Larry O’Hanlon

Key: WFS, Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev,World Fossil Society,Balanced Rocks , San Andreas

December 31st, 2015

December 31st, 2015  Riffin

Riffin