@WFS,World Fossil Society, Athira,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

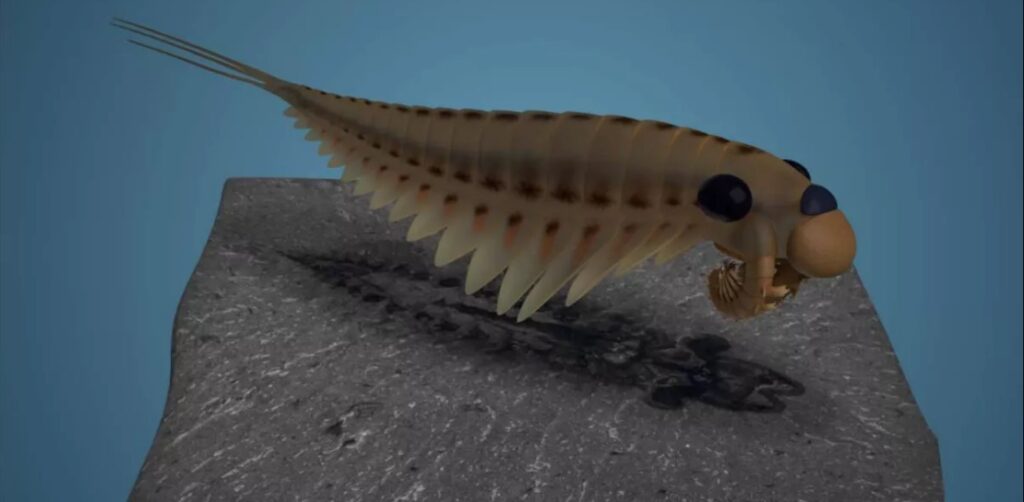

Discoveries at a major new fossil site in Morocco suggest giant arthropods — relatives of modern creatures including shrimps, insects and spiders — dominated the seas 470 million years ago.

Early evidence from the site at Taichoute, once undersea but now a desert, records numerous large “free-swimming” arthropods.

More research is needed to analyse these fragments, but based on previously described specimens, the giant arthropods could be up to 2m long.

An international research team say the site and its fossil record are very different from other previously described and studied Fezouata Shale sites from 80km away.

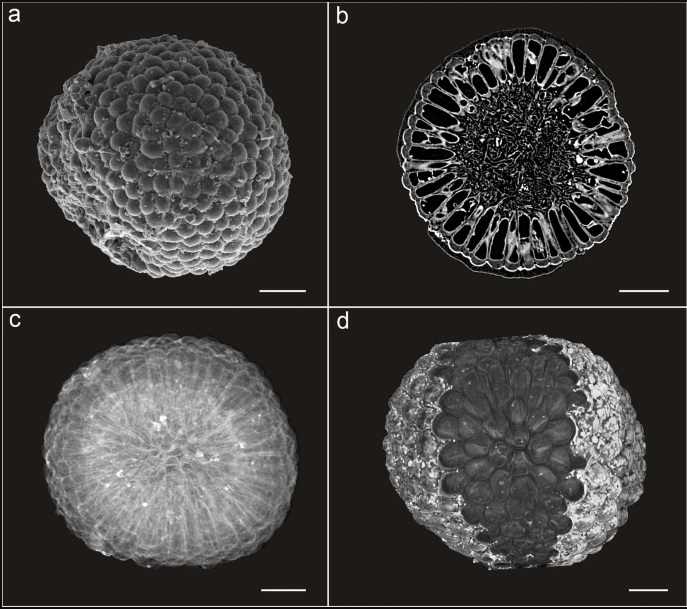

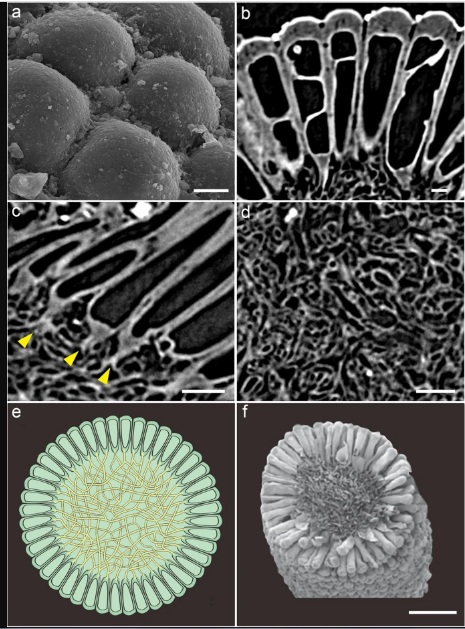

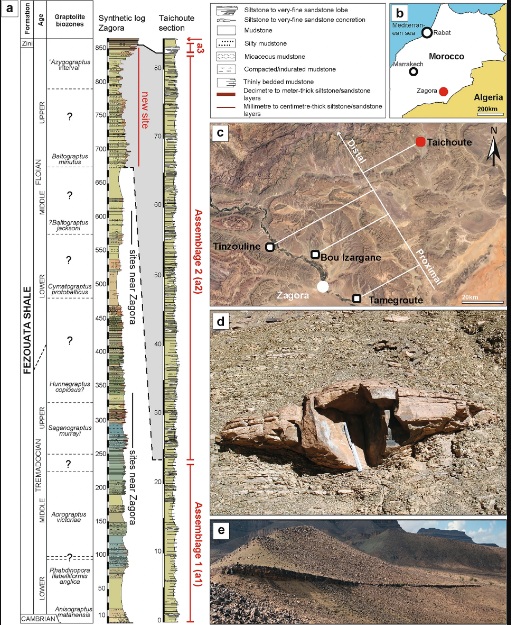

(a) Stratigraphic column for the Lower Ordovician Fezouata Shale and Zini formations including the Taichoute locality divided into three fossil assemblages. The red arrow in (a) indicates an accumulation level of brachiopods and bryozoans at the top of the Taichoute section. (b) Zoom on the Zagora Region where the Fezouata Shale was discovered. (c) Taichoute is the most distal site in the depositional environment of the Fezouata Shale. (d) Concretion from the Zagora region. (e) A large lobe from the Fezouata Shale in the upper part of the succession (a3) and interpreted as a density-flow deposit.

They say Taichoute (considered part of the wider “Fezouata Biota”) opens new avenues for paleontological and ecological research.

“Everything is new about this locality — its sedimentology, paleontology, and even the preservation of fossils — further highlighting the importance of the Fezouata Biota in completing our understanding of past life on Earth,” said lead author Dr Farid Saleh, from the University of Lausanne and and Yunnan University.

Dr Xiaoya Ma, from the University of Exeter and Yunnan University, added: “While the giant arthropods we discovered have not yet been fully identified, some may belong to previously described species of the Fezouata Biota, and some will certainly be new species.

“Nevertheless, their large size and free-swimming lifestyle suggest they played a unique role in these ecosystems.”

The Fezouata Shale was recently selected as one of the 100 most important geological sites worldwide because of its importance for understanding the evolution during the Early Ordovician period, about 470 million years ago.

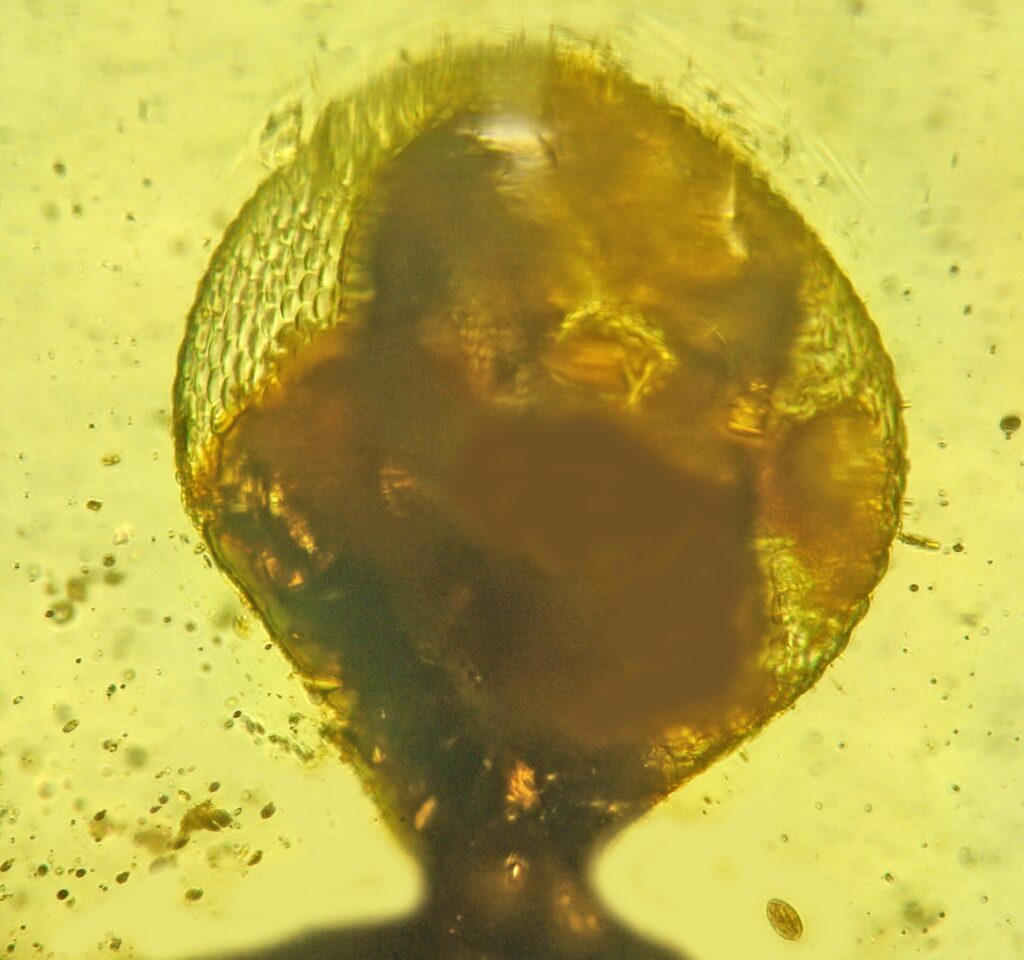

Fossils discovered in these rocks include mineralised elements (eg shells), but some also show exceptional preservation of soft parts such as internal organs, allowing scientists to investigate the anatomy of early animal life on Earth.

Animals of the Fezouata Shale, in Morocco’s Zagora region, lived in a shallow sea that experienced repeated storm and wave activities, which buried the animal communities and preserved them in place as exceptional fossils.

However, nektonic (or free-swimming) animals remain a relatively minor component overall in the Fezouata Biota.

The new study reports the discovery of the Taichoute fossils, preserved in sediments that are a few million years younger than those from the Zagora area and are dominated by fragments of giant arthropods.

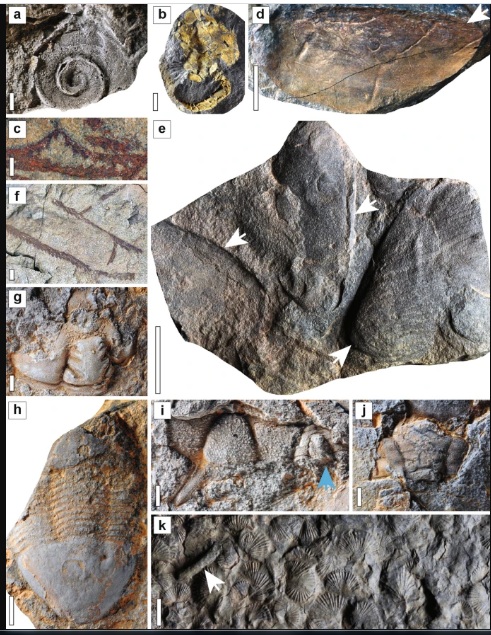

Fossils from the Taichoute locality (a1: A–C, a2: D–F, a3: G–J). (a) The gastropod Lesueurilla prima. (b) The solutan echinoderm Plasiacystis mobilis. (c) The graptolite Baltograptus gr. deflexus. (d–e) Giant euarthropod carapaces indicated with white arrows. (d) Carapace likely belonging to previously documented bivalved arthropods from the Fezouata Biota59. (e) Two incomplete but tapering carapaces (left and center) adjacent to a structure that bears possible resemblance to a block of radiodont setal blades (right), consisting of a series of parallel elongated blades a few millimetres wide separated by slight changes in sediment level and/or by intervening sediment, with an overall tapering outline, similar to the setal blade blocks of hurdiids such as Hurdia from the Burgess Shale60. (f) The multiramous graptolite Holograptus sp. (g) The calymenid trilobite Colpocoryphe cf. thorali. (h) The illaenid trilobite Ectillaenus? sp. (i) The calymenid trilobite Neseuretus cf. attenuatus (blue arrow) and Lichidae gen. indet. (to the left of the blue arrow). (j) A dalmanitid trilobite, subfamily Zeliszkellinae. (k) Accumulations of specimens of a new genus of orthidine brachiopod and bryozoans (white arrow) on top of a3. Scale bars = 5 mm in a, f, g, h, i, j; 10 mm in b, c and k; 25 mm in d; 50 mm in e. By order from a to j: AA.TAI2.OI.9; ML20-259,357; AA.TAI3.OI.2; AA.TAI6.OI.1; AA.TAI6.OI.2; AA.TAI6.OI.6; AA.TAI13.OI.1; AA.TAI13.OI.2; AA.TAI13.OI.3; AA.TAI13.OI.4; AA.TAI14.OI.1. All specimens are housed in the Marrakech Collections of the Cadi Ayyad University.

“Carcasses were transported to a relatively deep marine environment by underwater landslides, which contrasts with previous discoveries of carcass preservation in shallower settings, which were buried in place by storm deposits,” said Dr Romain Vaucher, from the University of Lausanne.

Professor Allison Daley, also from the University of Lausanne, added: “Animals such as brachiopods are found attached to some arthropod fragments, indicating that these large carapaces acted as nutrient stores for the seafloor dwelling community once they were dead and lying on the seafloor.”

Dr Lukáš Laibl, from the Czech Academy of Sciences, who had the opportunity to participate in the initial fieldwork, said: “Taichoute is not only important due to the dominance of large nektonic arthropods.

“Even when it comes to trilobites, new species so far unknown from the Fezouata Biota are found in Taichoute.”

Dr Bertrand Lefebvre, from the University of Lyon, who is the senior author on the paper, and who has been working on the Fezouata Biota for the past two decades, concluded: “The Fezouata Biota keeps surprising us with new unexpected discoveries.”

The paper, published in the journal Scientific Reports, is entitled: “New fossil assemblages from the Early Ordovician Fezouata Biota.”

Journal Reference:

- Farid Saleh, Romain Vaucher, Muriel Vidal, Khadija El Hariri, Lukáš Laibl, Allison C. Daley, Juan Carlos Gutiérrez-Marco, Yves Candela, David A. T. Harper, Javier Ortega-Hernández, Xiaoya Ma, Ariba Rida, Daniel Vizcaïno, Bertrand Lefebvre. New fossil assemblages from the Early Ordovician Fezouata Biota. Scientific Reports, 2022; 12 (1) DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-25000-z

Source: Science Daily

@WFS,World Fossil Society, Athira,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev

December 19th, 2022

December 19th, 2022  Riffin

Riffin