WFS,World Fossil Society,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev, Athira

For decades, paleontologists have debated whether dinosaurs were warm-blooded, like modern mammals and birds, or cold-blooded, like modern reptiles. Knowing whether dinosaurs were warm- or cold-blooded could give us hints about how active they were and what their everyday lives were like, but the methods to determine their warm- or cold-bloodedness — how quickly their metabolisms could turn oxygen into energy — were inconclusive. But in a new paper in Nature, scientists are unveiling a new method for studying dinosaurs’ metabolic rates, using clues in their bones that indicated how much the individual animals breathed in their last hour of life.

“This is really exciting for us as paleontologists — the question of whether dinosaurs were warm- or cold-blooded is one of the oldest questions in paleontology, and now we think we have a consensus, that most dinosaurs were warm-blooded,” says Jasmina Wiemann, the paper’s lead author and a postdoctoral researcher at the California Institute of Technology.

“The new proxy developed by Jasmina Wiemann allows us to directly infer metabolism in extinct organisms, something that we were only dreaming about just a few years ago. We also found different metabolic rates characterizing different groups, which was previously suggested based on other methods, but never directly tested,” says Matteo Fabbri, a postdoctoral researcher at the Field Museum in Chicago and one of the study’s authors.

People sometimes talk about metabolism in terms of how easy it is for someone to stay in shape, but at its core, “metabolism is how effectively we convert the oxygen that we breathe into chemical energy that fuels our body,” says Wiemann, who is affiliated with Yale University and the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

Animals with a high metabolic rate are endothermic, or warm-blooded; warm-blooded animals like birds and mammals take in lots of oxygen and have to burn a lot of calories in order to maintain their body temperature and stay active. Cold-blooded, or ectothermic, animals like reptiles breathe less and eat less. Their lifestyle is less energetically expensive than a hot-blooded animal’s, but it comes at a price: cold-blooded animals are reliant on the outside world to keep their bodies at the right temperature to function (like a lizard basking in the sun), and they tend to be less active than warm-blooded creatures.

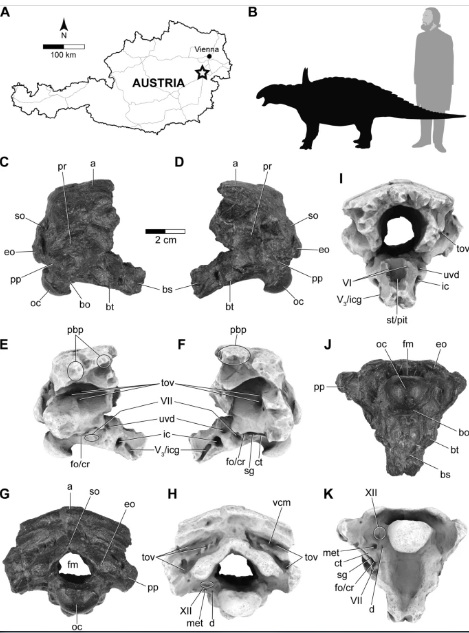

With birds being warm-blooded and reptiles being cold-blooded, dinosaurs were caught in the middle of a debate. Birds are the only dinosaurs that survived the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous, but dinosaurs (and by extension, birds) are technically reptiles — outside of birds, their closest living relatives are crocodiles and alligators. So would that make dinosaurs warm-blooded, or cold-blooded?

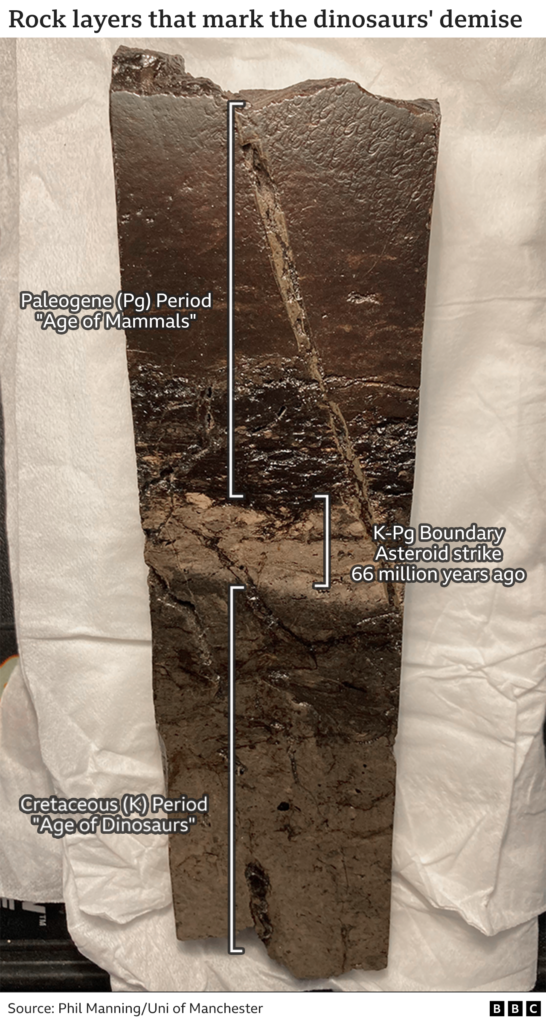

Scientists have tried to glean dinosaurs’ metabolic rates from chemical and osteohistological analyses of their bones. “In the past, people have looked at dinosaur bones with isotope geochemistry that basically works like a paleo-thermometer,” says Wiemann — researchers examine the minerals in a fossil and determine what temperatures those minerals would form in. “It’s a really cool approach and it was really revolutionary when it came out, and it continues to provide very exciting insights into the physiology of extinct animals. But we’ve realized that we don’t really understand yet how fossilization processes change the isotope signals that we pick up, so it is hard to unambiguously compare the data from fossils to modern animals.”

Another method for studying metabolism is growth rate. “If you look at a cross section of dinosaur bone tissue, you can see a series of lines, like tree rings, that correspond to years of growth,” says Fabbri. “You can count the lines of growth and the space between them to see how fast the dinosaur grew. The limit relies on how you transform growth rate estimates into metabolism: growing faster or slower can have more to do with the animal’s stage in life than with its metabolism, like how we grow faster when we’re young and slower when we’re older.”

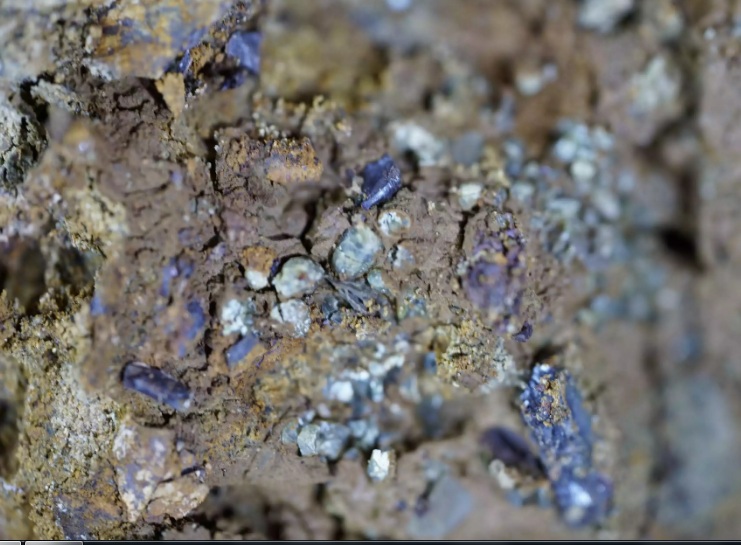

The new method proposed by Wiemann, Fabbri, and their colleagues doesn’t look at the minerals present in bone or how quickly the dinosaur grew. Instead, they look at one of the most basic hallmarks of metabolism: oxygen use. When animals breathe, side products form that react with proteins, sugars, and lipids, leaving behind molecular “waste.” This waste is extremely stable and water-insoluble, so it’s preserved during the fossilization process. It leaves behind a record of how much oxygen a dinosaur was breathing in, and thus, its metabolic rate.

The researchers looked for these bits of molecular waste in dark-colored fossil femurs, because those dark colors indicate that lots of organic matter are preserved. They examined the fossils using Raman and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy — “these methods work like laser microscopes, we can basically quantify the abundance of these molecular markers that tell us about the metabolic rate,” says Wiemann. “It is a particularly attractive method to paleontologists, because it is non-destructive.”

The team analyzed the femurs of 55 different groups of animals, including dinosaurs, their flying cousins the pterosaurs, their more distant marine relatives the plesiosaurs, and modern birds, mammals, and lizards. They compared the amount of breathing-related molecular byproducts with the known metabolic rates of the living animals and used those data to infer the metabolic rates of the extinct ones.

The team found that dinosaurs’ metabolic rates were generally high. There are two big groups of dinosaurs, the saurischians and the ornithischians — lizard hips and bird hips. The bird-hipped dinosaurs, like Triceratops and Stegosaurus, had low metabolic rates comparable to those of cold-blooded modern animals. The lizard-hipped dinosaurs, including theropods and the sauropods — the two-legged, more bird-like predatory dinosaurs like Velociraptor and T. rex and the giant, long-necked herbivores like Brachiosaurus — were warm- or even hot-blooded. The researchers were surprised to find that some of these dinosaurs weren’t just warm-blooded — they had metabolic rates comparable to modern birds, much higher than mammals. These results complement previous independent observations that hinted at such trends but could not provide direct evidence, because of the lack of a direct proxy to infer metabolism.

These findings, the researchers say, can give us fundamentally new insights into what dinosaurs’ lives were like.

“Dinosaurs with lower metabolic rates would have been, to some extent, dependent on external temperatures,” says Wiemann. “Lizards and turtles sit in the sun and bask, and we may have to consider similar ‘behavioral’ thermoregulation in ornithischians with exceptionally low metabolic rates. Cold-blooded dinosaurs also might have had to migrate to warmer climates during the cold season, and climate may have been a selective factor for where some of these dinosaurs could live.”

On the other hand, she says, the hot-blooded dinosaurs would have been more active and would have needed to eat a lot. “The hot-blooded giant sauropods were herbivores, and it would take a lot of plant matter to feed this metabolic system. They had very efficient digestive systems, and since they were so big, it probably was more of a problem for them to cool down than to heat up.” Meanwhile, the theropod dinosaurs — the group that contains birds — developed high metabolisms even before some of their members evolved flight.

“Reconstructing the biology and physiology of extinct animals is one of the hardest things to do in paleontology. This new study adds a fundamental piece of the puzzle in understanding the evolution of physiology in deep time and complements previous proxies used to investigate these questions. We can now infer body temperature through isotopes, growth strategies through osteohistology, and metabolic rates through chemical proxies,” says Fabbri.

In addition to giving us insights into what dinosaurs were like, this study also helps us better understand the world around us today. Dinosaurs, with the exception of birds, died out in a mass extinction 65 million years ago when an asteroid struck the Earth. “Having a high metabolic rate has generally been suggested as one of the key advantages when it comes to surviving mass extinctions and successfully radiating afterwards,” says Wiemann — some scientists have proposed that birds survived while the non-avian dinosaurs died because of the birds’ increased metabolic capacity. But this study, Wiemann says, helps to show that this isn’t true: many dinosaurs with bird-like, exceptional metabolic capacities went extinct.

“We are living in the sixth mass extinction,” says Wiemann, “so it is important for us to understand how modern and extinct animals physiologically responded to previous climate change and environmental perturbations, so that the past can inform biodiversity conservation in the present and inform our future actions.”

Journal Reference:

- Jasmina Wiemann, Iris Menéndez, Jason M. Crawford, Matteo Fabbri, Jacques A. Gauthier, Pincelli M. Hull, Mark A. Norell, Derek E. G. Briggs. Fossil biomolecules reveal an avian metabolism in the ancestral dinosaur. Nature, 2022; DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04770-6

June 13th, 2022

June 13th, 2022  Riffin

Riffin