Ichthyosauria is a diverse clade of marine amniotes that spanned most of the Mesozoic. Until recently, most authors interpreted the fossil record as showing that three major extinction events affected this group during its history: one during the latest Triassic, one at the Jurassic–Cretaceous boundary (JCB), and one (resulting in total extinction) at the Cenomanian-Turonian boundary. The JCB was believed to eradicate most of the peculiar morphotypes found in the Late Jurassic, in favor of apparently less specialized forms in the Cretaceous. However, the record of ichthyosaurs from the Berriasian–Barremian interval is extremely limited, and the effects of the end-Jurassic extinction event on ichthyosaurs remains poorly understood.

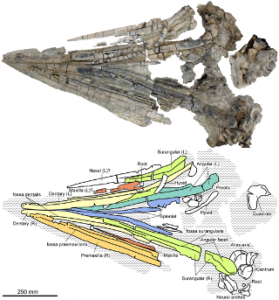

Based on new material from the Hauterivian of England and Germany and on abundant material from the Cambridge Greensand Formation, we name a new ophthalmosaurid, Acamptonectes densus gen. et sp. nov. This taxon shares numerous features with Ophthalmosaurus, a genus now restricted to the Callovian–Berriasian interval. Our phylogenetic analysis indicates that Ophthalmosauridae diverged early in its history into two markedly distinct clades, Ophthalmosaurinae and Platypterygiinae, both of which cross the JCB and persist to the late Albian at least. To evaluate the effect of the JCB extinction event on ichthyosaurs, we calculated cladogenesis, extinction, and survival rates for each stage of the Oxfordian–Barremian interval, under different scenarios. The extinction rate during the JCB never surpasses the background extinction rate for the Oxfordian–Barremian interval and the JCB records one of the highest survival rates of the interval.

The thunnosaurian ichthyosaur Ophthalmosaurus Seeley 1874 (family Ophthalmosauridae) is known from abundant material, most of it from the Oxford and Kimmeridge Clay formations of England and the Sundance Formation of the USA . The widely accepted stratigraphic range for this taxon is Callovian-Tithonian . However, the presence of Ophthalmosaurus in Lower Cretaceous sediments has been claimed twice in the modern literature: McGowan figured and discussed a humerus with three large distal facets from the Lower Cretaceous of Prince Patrick Island (Canada) that he referred toOphthalmosaurus sp. and McGowan & Motani mentioned the presence of isolated basioccipitals and humeri referable to Ophthalmosaurus in the early Cenomanian Cambridge Greensand Formation (which also includes a reworked late Albian fauna from the top of the Gault formation . These claims are, however, based on isolated material, and other ophthalmosaurid ichthyosaurs with three large distal humeral facets have been described from Cretaceous sediments since then, including Caypullisaurus and Maiaspondylus . Therefore, the presence of Ophthalmosaurus in the Cretaceous remains ambiguous at best. This has important consequences for the evolution and diversity of Early Cretaceous ophthalmosaurids. Indeed, until recently , all Middle and Late Jurassic ichthyosaurs were thought to have become extinct at the end of the Jurassic, at the Jurassic–Cretaceous boundary or during a more protracted extinction event that started during the Middle Jurassic . The JCB, which is associated with climate change , was therefore considered a major extinction event for ichthyosaurs, during which the successful “ophthalmosaurs” became extinct and replaced by what seemed to be less specialized forms. As summarized by Bakker

“The Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary extinction disrupted ichthyosaur history profoundly – the hyper-specialized ophthalmosaur clade disappears, and the only Early Cretaceous ichthyosaurs, the platypterygians, are much more generalized, with longer bodies, smaller eyes, larger teeth and heavier snouts.”

This contributed to the generally accepted idea that, despite their longevity (Olenekian, Early Triassic–Cenomanian, Late Cretaceous , ichthyosaurs underwent at least three major extinctions events throughout their history: during the Triassic–Jurassic boundary event , at the Jurassic–Cretaceous boundary (JCB), and during the Cenomanian–Turonian boundary event . However, the worldwide record of ichthyosaurs from the Berriasian–Barremian interval is extremely limited, making preservation biases an important parameter to consider when analyzing the Jurassic–Cretaceous extinction event . Yet, recent papers have highlighted the presence of some Late Jurassic ichthyosaurs in the Lower Cretaceous strata of South America, Europe, and Russia (Caypullisaurus , Aegirosaurus and the doubtful Yasykovia , respectively). The effect of the JCB extinction event on ichthyosaurs therefore remains poorly understood, whereas this extinction substantially affected several other groups related to the marine realm such as radiolarians, ammonites, marine crocodyliforms, pterosaurs, and plesiosaurs .

In order to examine the effect of the JCB extinction event on ichthyosaurs in detail and better understand the diversity and relationships of Early Cretaceous ophthalmosaurids, we:

- Re-evaluate the presence of Ophthalmosaurus in the Cretaceous of Europe

- Name a new Cretaceous ophthalmosaurid, Acamptonectes densus gen. et sp. nov., based on three well preserved specimens for a poorly sampled stage of the Early Cretaceous: the Hauterivian. This genus is also present in the Cambridge Greensand Formation (late Albian–early Cenomanian).

- Propose a robust phylogenetic hypothesis for the evolution of ophthalmosaurids, which diverged early in its history into two clades: Ophthalmosaurinae and Platypterygiinae. Both clades crossed the JCB and persisted to the late Albian at least

- Calculate cladogenesis, extinction, and survival rates for the Oxfordian–Aptian interval and show that the JCB event had a negligible impact on ichthyosaurs

Published in PLos One.

Valentin Fischer1,2*, Michael W. Maisch¤a, Darren Naish3,4,Ralf Kosma5, Jeff Liston6¤b, Ulrich Joger5, Fritz J. Krüger5,Judith Pardo Pérez7, Jessica Tainsh6, Robert M. Appleby†

1 Geology department, University of Liège, Liège, Belgium, 2 Paleontology Department, Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Brussels, Belgium,3 School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, United Kingdom, 4 School of Ocean and Earth Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom, 5 Staatliches Naturhistorisches Museum, Braunschweig, Germany, 6 Division of Environmental and Evolutionary Biology, School of Life Sciences, College of Medical Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland, 7 Institut für Geowissenschaften, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany

September 13th, 2012

September 13th, 2012  riffin

riffin

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: