A team of researchers from North Carolina State University and the Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) has found more evidence for the preservation of ancient dinosaur proteins, including reactivity to antibodies that target specific proteins normally found in bone cells of vertebrates. These results further rule out sample contamination, and help solidify the case for preservation of cells — and possibly DNA — in ancient remains.

Dr. Mary Schweitzer, professor of marine, earth and atmospheric sciences with a joint appointment at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, first discovered what appeared to be preserved soft tissue in a 67-million-year-oldTyrannosaurus Rex in 2005. Subsequent research revealed similar preservation in an even older (about 80-million-year-old)Brachylophosaurus canadensis. In 2007 and again in 2009, Schweitzer and colleagues used chemical and molecular analyses to confirm that the fibrous material collected from the specimens was collagen.

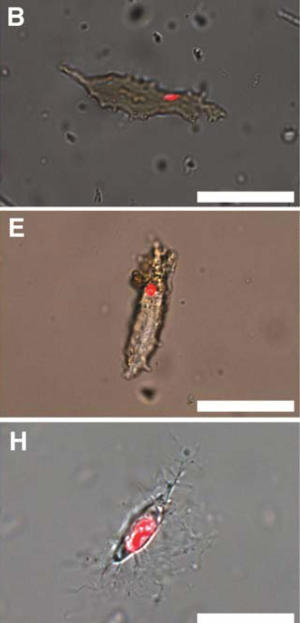

Schweitzer’s next step was to find out if the star-shaped cellular structures within the fibrous matrix were osteocytes, or bone cells. Using techniques including microscopy, histochemistry and mass spectrometry, Schweitzer demonstrates that these cellular structures react to specific antibodies, including one — a protein known as PHEX — that is found in the osteocytes of living birds. The findings appear online in Bone and were presented last week at the annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.

“The PHEX finding is important because it helps to rule out sample contamination,” Schweitzer says. “Some of the antibodies that we used will react to proteins found in other vertebrate cells, but none of the antibodies react to microbes, which supports our theory that these structures are surviving osteocytes. Additionally, the antibody to PHEX will only recognize and bind to one specific site only found in mature bone cells from birds. These antibodies don’t react to other proteins or cells. Because so many other lines of evidence support the dinosaur/bird relationship, finding these proteins helps make the case that these structures are dinosaurian in origin.”

Schweitzer and her team also tested for the presence of DNA within the cellular structures, using an antibody that only binds to the “backbone” of DNA. The antibody reacted to small amounts of material within the “cells” of both the T. rex and the B. canadensis. To rule out the presence of microbes, they used an antibody that binds histone proteins, which bind tightly to the DNA of everything except microbes, and got another positive result. They then ran two other histochemical stains which fluoresce when they attach to DNA molecules. Those tests were also positive. These data strongly suggest that the DNA is original, but without sequence data, it is impossible to confirm that the DNA is dinosaurian.

“The data thus far seem to support the theory that these structures can be preserved over time,” Schweitzer says. “Hopefully these findings will give us greater insight into the processes of evolutionary change.”

Dr. Marshall Bern, from PARC, performed the mass spectrometry. Former NC State doctoral student Timothy Cleland and research assistant Wenxia Zheng also contributed to the work, which was funded by grants from the National Science Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

October 26th, 2012

October 26th, 2012  Riffin

Riffin

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: