The pectoral and pelvic girdles support paired fins and limbs, and have transformed significantly in the diversification of gnathostomes or jawed vertebrates (including osteichthyans, chondrichthyans, acanthodians and placoderms). For instance, changes in the pectoral and pelvic girdles accompanied the transition of fins to limbs as some osteichthyans (a clade that contains the vast majority of vertebrates – bony fishes and tetrapods) ventured from aquatic to terrestrial environments. The fossil record shows that the pectoral girdles of early osteichthyans (e.g., Lophosteus, Andreolepis, Psarolepis and Guiyu) retained part of the primitive gnathostome pectoral girdle condition with spines and/or other dermal components. However, very little is known about the condition of the pelvic girdle in the earliest osteichthyans. Living osteichthyans, like chondrichthyans (cartilaginous fishes), have exclusively endoskeletal pelvic girdles, while dermal pelvic girdle components (plates and/or spines) have so far been found only in some extinct placoderms and acanthodians. Consequently, whether the pectoral and pelvic girdles are primitively similar in osteichthyans cannot be adequately evaluated, and phylogeny-based inferences regarding the primitive pelvic girdle condition in osteichthyans cannot be tested against available fossil evidence.

The gnathostomes or jawed vertebrates comprise the extant osteichthyans (bony fishes and tetrapods) and chondrichthyans (cartilaginous fishes) along with the extinct placoderms and acanthodians . Girdle-supported paired fins and limbs characterize all jawed vertebrates, and have undergone significant transformation in the course of gnathostome diversification. The pectoral girdles of gnathostomes primitively combine dermal and endoskeletal elements, as in jawless osteostracans even though the osteostracan pectoral girdles are fused to the cranium. For instance, the pectoral girdle in crown osteichthyans (actinopterygians and sarcopterygians) has an endoskeletal scapulocoracoid attached to the inner surface of the cleithrum (one of the encircling dermal bones of the pectoral girdle). However, the primitive condition for pelvic girdles is less clear, resulting from the scarcity of articulated early gnathostome postcrania and the absence of girdle-supported pelvic fins in all known jawless fishes. Both living osteichthyans and chondrichthyans have exclusively endoskeletal pelvic girdles . Until recently, the presence of pelvic girdles with substantial dermal components (large dermal plates) was thought to be restricted to some placoderms (arthrodires, ptyctodonts, acanthothoracids and antiarchs) while pelvic fin spines alone were found in some acanthodians . The purported monophyly of both of these fossil gnathostome ‘classes’ is currently under scrutiny, with most recent phylogenies assigning some or all acanthodians to the osteichthyan stem , while resolving the placoderms (either as a monophyletic group or as a paraphyletic assemblage) at the base of the jawed vertebrate radiation. Inferences from these phylogenies would predict that stem osteichthyans more crownward than Acanthodes should have at most the pelvic girdles similar to those in acanthodians (i.e., an endoskeletal girdle with a dermal fin spine). Until now, the earliest osteichthyan materials have yielded very little information regarding the primitive condition of pelvic girdles among osteichthyans, making it difficult to test phylogeny-based inferences against the known fossil record or to explore how and when the living osteichthyans may have acquired their exclusively endoskeletal pelvic girdles.

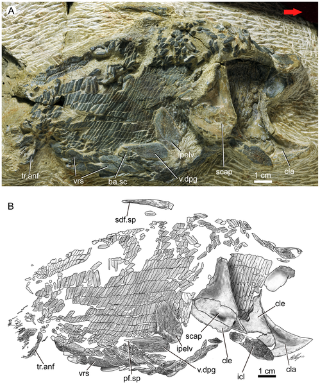

As the first known occurrence in any osteichthyans, here we describe pelvic girdles with substantial dermal components (plates and spines) in two early bony fishes, Guiyu oneiros andPsarolepis romeri , from Yunnan, China. Guiyu and Psarolepis have been placed as stem sarcopterygians in earlier studies , even though they manifested combinations of features found in both sarcopterygians and actinopterygians (e.g. pectoral girdle structures, the cheek and operculo-gular bone pattern, and scale articulation). When Guiyu was first described based on an exceptionally well-preserved holotype specimen, it also revealed a combination of osteichthyan and non-osteichthyan features, including spine-bearing pectoral girdles and spine-bearing median dorsal plates found in non-osteichthyan gnathostomes as well as cranial morphology and derived macromeric squamation found in crown osteichthyans. In addition, Guiyuprovided strong corroboration for the attempted restoration of Psarolepis romeri based on disarticulated cranial, cheek plate, shoulder girdle and scale materials . The incongruent distribution of Guiyu and Psarolepis features across different groups (actinopteryians vs sarcopterygians, osteichthyans vs non-osteichthyans) poses special challenges to attempts at polarizing the plesiomorphic osteichthyan and gnathostome characters and reconstructing osteichthyan morphotype . The phylogenetic analysis in Zhu et al. assigned two possible positions for Psarolepis, either as a stem sarcopterygian or as a stem osteichthyan. Basden et al. suggested that Psarolepis is more likely a stem sarcopterygian based on the comparison of braincase morphology with an actinopterygian-like osteichthyan Ligulalepis. The phylogenetic analysis in Zhu et al. placed Guiyu in a cluster with Psarolepis and Achoania as stem sarcopterygians, with Meemannia and Ligulalepis as more basal sarcopterygians, and Andreolepis and Lophosteus as stem osteichthyans.

Although previous studies of Guiyu and Psarolepis have advanced our understanding of early osteichthyan morphologies beyond what was previously known from Andreolepis, Lophosteus ,Ligulalepis and Dialipina , no pelvic girdle components were identified or described at the time, and the primitive condition of pelvic girdles in osteichthyans remained unknown until recently. The situation started to change when a new articulated specimen of Guiyu oneiros was collected from the Late Ludlow (Silurian) Kuanti Formation, Yunnan, China. Observations of this new specimen, re-examination of the holotype of Guiyu oneiros, and studies of previously unidentified disarticulated specimens of Psarolepis form the basis for the finding reported below. As the first evidence for the presence of dermal pelvic girdles in osteichthyans, the pelvic girdles in Guiyu and Psarolepis reveal an unexpected morphology that stands in stark contrast to the inferences from published phylogenetic analyses (except for one of two alternative positions of Psarolepis in Zhu et al. , and appear to resemble those of placoderms rather than either the acanthodians or, indeed, any other previously known osteichthyans.

Min Zhu1*, Xiaobo Yu1,2, Brian Choo1, Qingming Qu1,3,Liantao Jia1, Wenjin Zhao1, Tuo Qiao1, Jing Lu1

1 Key Laboratory of Evolutionary Systematics of Vertebrates, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 2 Department of Biological Sciences, Kean University, New Jersey, United States of America, 3 Subdepartment of Evolutionary Organismal Biology, Department of Physiology and Developmental Biology, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

October 22nd, 2012

October 22nd, 2012  riffin

riffin

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: