WFS,Riffin T Sajeev,Russel T Sajeev,World Fossil Society

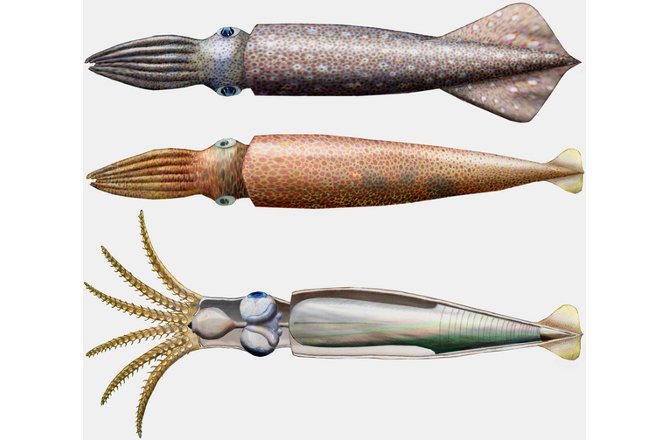

Three extremely rare fossil specimens of an extinct squidlike animal provide new evidence of the 10-armed creature’s body structure and suggest that it may have been a swift swimmer, a new study finds.

Acanthoteuthis is a cephalopod, part of the ocean-dwelling group that includes modern octopus, squid and cuttlefish, with an evolutionary history spanning 500 million years. But even though cephalopods have been around for a long time, unlike many other extinct animals, they don’t leave much of themselves behind in the fossil record. Their soft bodies don’t preserve well, and the isolated bits that do fossilize tell only a partial story of what the living animal might have looked like.

Acanthoteuthis belongs to a group of cephalopods called belemnites, which are particularly abundant in the fossil record — or at least a small part of them is. Belemnites had tough internal shells capped by hard parts called “rostra,” which preserve well, as roughly bullet-shaped fossils. Rostra fossils are plentiful, and marks on them can even reveal traces of where the belemnites’ fins attached to the mantle, the cone-shaped, muscular part of the body that forces water through a siphon for jet-propelled swimming.

So what kept these specimens in such good condition and preserved so much of their bodies? Christian Klug, co-author of the new study and a curator at the Paleontological Institute and Museum at the University of Zurich, said the reason had to do with the site in Solnhofen, Germany, where the fossils were found.

“Solnhofen and its surroundings are world-renowned for exceptionally preserved fossils,” Klug told Live Science in an email. “These fossils were embedded in fine-grained sediments in more-or-less quiet water lagoons between coral reefs. Additionally, microbial mats stabilized the sediments, guaranteeing perfectly flat bedding.” Rapid burial and certain chemical conditions in the soil would also have played a part in the preservation, Klug added.

The discoveries of the well-preserved Acanthoteuthis specimens were certainly very special, and Klug and his colleagues were eager to see what the fossils might reveal. “Since we knew that the material was important, we figured we should get the most out of it,” he said.

February 21st, 2016

February 21st, 2016  Riffin

Riffin

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: