An early warning system against tsunamis has been developed and tailored for the need of the Mediterranean, but preparedness on the ground is paramount to ensuring peoples’ safety.

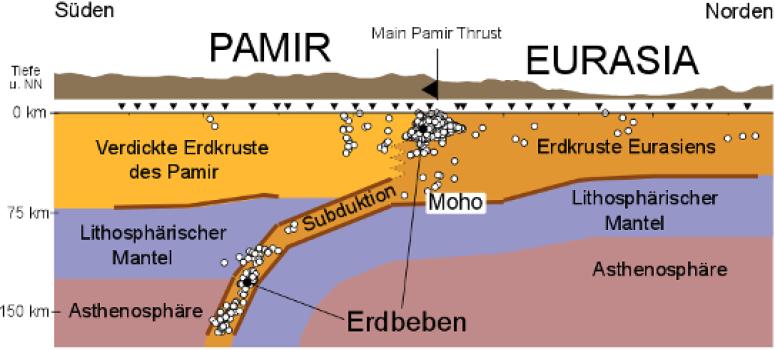

When a coastal area is about to be hit by the waves of a tsunami, time is everything. The earlier we know where and when it is going to hit the coast, the more chances there are to evacuate the area. Early warning systems play a crucial role. Until now, seismic signals were used to issue such warning. These are subsequently confirmed or cleared by measuring sea level height. This approach stems from the fact that shallow submarine earthquakes exceeding a given magnitude are the most likely causes of tsunamis.

tsunami

More recently, an EU funded project called NEARESTfound a better way of identifying a tsunami threat at early stage. “To do this we developed a new device we called tsunameter that we put as close as possible to those places where we know that is very likely a tsunami is generated,” says Francesco Chierici, who is the project coordinator and also works as a researcher the Radio Astronomy Institute (IRA), in Bologna, Italy. This tsunameter can be placed close to the geological faults that are responsible for the earthquake and, accordingly, for tsunamis. Detecting a tsunami near its source is crucial “expecially in peculiar environments such as the Mediterranean where the tsunami are generated very close to the coasts,” says Chierici.

Every device is connected with a surface buoy and consists of a set of instruments collecting several kinds of data. These include local acceleration and pressure of water, seismic waves, and, in particular, the acoustic waves generated by tsunamis.With this information, actual tsunamis can be distinguished from the background noise, “using a specific mathematical algorithm” which is interpreting the data. Under the project, the tsunameter had been tested for a year off the Gulf of Cadiz in Spain, at water depth of 3,200 metres. Since the project was completed, in March 2010, the tsunameters are now tested in a new research programme called Multidisciplinary Oceanic Information SysTem (MOIST), run by the Italian National Institute of Geophysics and Vulcanology(INGV) in Rome.

The idea of using acoustic waves as tsunami signal is effective, according toStefano Tinti, professor of geology at the University of Bologna, Italy, and an expert in tsunamis. “Their speed of propagation is slower than that of seismic waves, but still quicker than that of the tsunami,” he said. The problem is the technology “is still in an experimental stage and it’s not so easy to separate the hydroacoustic signal from the others when the detector is so close to the source.”

Another issue is the cost of installation and maintenance. “Off-shore detection systems are more expensive than coastal ones,” he adds. Tinti also believes it could be more effective to use the many islands spread around the Mediterranean. “The detection could be of no use in terms of warning system for the very point where the detection takes place,” he contends, “but it is still very useful for other areas of the coast.” The difficulties related to having a costly off-shore observation system are confirmed by Fernando Carrilho of the Portuguese Marine and Atmosphere Institute (IPMA), which was a project partner. When the Portuguese government decided to build a national tsunami early warning system, he explains, experts opted for a cheaper coastal sea-level observation system.

Other experts point out to issues related to providing a timely warning to the population. “Measurements would need to be far enough from the land to be affected to give enough time to raise the alarm,” says Philippe Blondel, acoustic remote sensing expert at the department of physics of the University of Bath, UK. Apart from which early warning system you choose, the difference between saving lives or not is preparedness. “For example, if the Vesuvius erupts and a flank collapses into the sea, this would affect the millions of people in and around Naples, in Italy. Even with the best organisation, there are only so many roads available for people to get away in a hurry,” says Blondel.

A different level of preparedness is required in the Mediterranean, compared to the situation in Japan and United States where “as soon as a tsunami is confirmed as being underway, alarms will sound in all communities likely to be affected,” Blondel explains. Clear evacuation routes have been signposted, he believes, and everybody has been trained to know where to go. He quotes the example of the US West coast, where many long, romantic sandy beaches now have signs every few hundred meters say

September 7th, 2013

September 7th, 2013  Riffin

Riffin

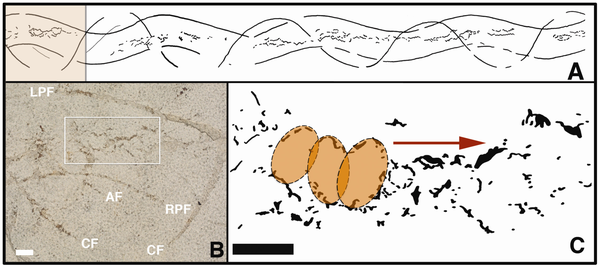

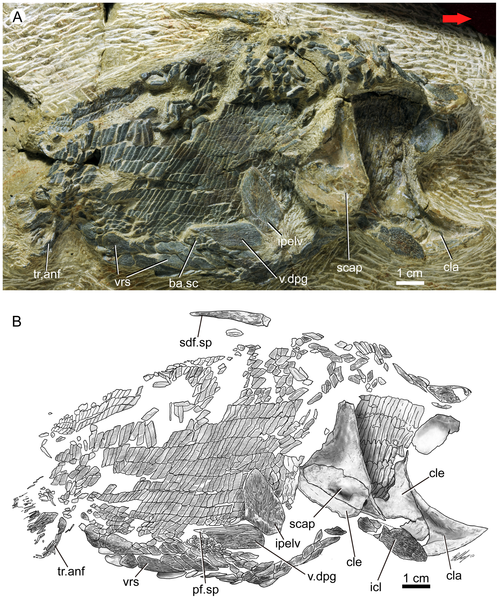

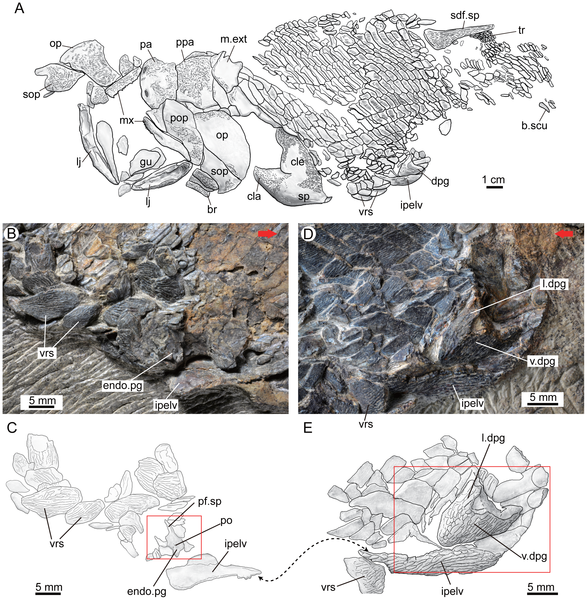

![Figure 4. Guiyu oneiros Zhu et al., 2009. show more A. Close-up of the three median dorsal plates (Md1-Md3) of the holotype V15541. B–C. A disarticulated third median dorsal plate (Md3) bearing the first dorsal fin spine in external (B) and internal (C) views, V17914.2. D. A disarticulated third median dorsal plate (Md3) in external view, V17914.3. E. Revised restoration of Guiyu oneiros in lateral view, based on [24] for the cranial portion, and new data in this work. Abbreviations: Md1–Md3, first to third median dorsal plates, with the third bearing the first dorsal fin spine and the endoskelatal basal plate. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035103.g004](http://worldfossilsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/121219174150-large4.png)